As a child I loved everything about our Christmas tree. I loved picking it out with my father on a cold winter day. I loved bringing it into the home a few days before Christmas to let it warm up so the branches could thaw out. I loved the smell. I loved helping with the lights and then adding ornaments and perhaps tinsel and strings of popcorn.

You can imagine my disappointment when I was told that Christmas trees were an adaptation of a pagan custom. Likewise, you can imagine my delight when I read recently that the “pagan custom” story was in fact a myth. As Emily McGowan writes:

You can imagine my disappointment when I was told that Christmas trees were an adaptation of a pagan custom. Likewise, you can imagine my delight when I read recently that the “pagan custom” story was in fact a myth. As Emily McGowan writes:

Though many in the modern period have sought to trace the Christmas tree back to pre-Christian paganism, historians now acknowledge this is a myth. Others have attempted to link it to legends about Saint Boniface or Martin Luther, but these stories have no basis in history either. Our best historians think the Christmas tree tradition developed in the medieval period. During that time most people couldn’t read or write, so plays were put on to teach biblical stories. One feature of such plays was a paradise tree representing the tree of knowledge (Genesis 2:9 ). In the play, the tree symbolized both the fallenness of humankind and the cross, the “tree” that brought us salvation. They decorated the paradise tree with apples for the fall and round pastry wafers for the Eucharist—the body of Christ that saves us. Interestingly, the Feast of Adam and Eve fell on December 24, so the public display of the paradise tree coincided with the day before the start of Christmas.*

The Bible Project podcast on trees confirms this. Trees in Scripture are not just interesting botanically as we encounter oak, cedar, juniper, and many other kinds. They are important as symbols of humanity and of our relationship with God.

The Bible Project podcast on trees confirms this. Trees in Scripture are not just interesting botanically as we encounter oak, cedar, juniper, and many other kinds. They are important as symbols of humanity and of our relationship with God.

Psalm 1 famously compares a righteous, flourishing human to a tree by water that abounds in fruit. The wood from trees elsewhere plays important roles in salvation. The ark that saved Noah and his family was made of wood. Sacrifices were often burned with wood.

So to bring a tree into our homes and celebrate it is no pagan holdover but a reminder of our salvation.

For as Emily McGowin reminds us, while humanity was banished from the garden so that we would be cut off from the tree of life, because of Christ we now have full and free access to the new tree of life—the cross.

—

*Emily Hunter McGowin, Christmas (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2023), p. 74.

Image by 🌸♡💙♡🌸 Julita 🌸♡💙♡🌸 from Pixabay

What we seldom notice, however, is that there is another Christmas story in Matthew, another version of how Jesus was born to Mary and Joseph. This overlooked account is squeezed between a list of Jesus’ ancestors and the familiar story. Here it is:

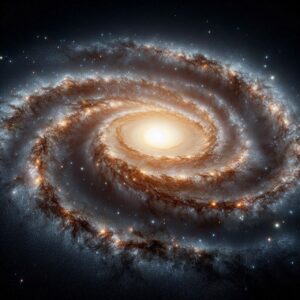

What we seldom notice, however, is that there is another Christmas story in Matthew, another version of how Jesus was born to Mary and Joseph. This overlooked account is squeezed between a list of Jesus’ ancestors and the familiar story. Here it is: Matthew’s grand, sweeping overview before the intimate portrait of Mary and Joseph is like a movie that begins with the whole universe in view. Then the camera moves faster than the speed of light through billions of galaxies to pause momentarily on the Milky Way before finding our solar system, racing past Saturn and Jupiter to Earth, then the Middle East, and zeroing in on a room in a Palestinian hovel.

Matthew’s grand, sweeping overview before the intimate portrait of Mary and Joseph is like a movie that begins with the whole universe in view. Then the camera moves faster than the speed of light through billions of galaxies to pause momentarily on the Milky Way before finding our solar system, racing past Saturn and Jupiter to Earth, then the Middle East, and zeroing in on a room in a Palestinian hovel. His overall structure has merit. He begins with what he calls the cognitive revolution of perhaps 40,000 years ago. Sapiens expanded their inventions, art, and language far beyond any other animal. This allowed for cooperation that made up for deficiencies in size, strength, and speed.

His overall structure has merit. He begins with what he calls the cognitive revolution of perhaps 40,000 years ago. Sapiens expanded their inventions, art, and language far beyond any other animal. This allowed for cooperation that made up for deficiencies in size, strength, and speed.

Psalms is a different book with a different context—one aspect of which is that of bringing all our emotions, concerns, praise, frustrations, thanksgiving, and sorrows to God in worship. In fact, more than a third of all psalms are laments, more than any other type of psalm.

Psalms is a different book with a different context—one aspect of which is that of bringing all our emotions, concerns, praise, frustrations, thanksgiving, and sorrows to God in worship. In fact, more than a third of all psalms are laments, more than any other type of psalm.