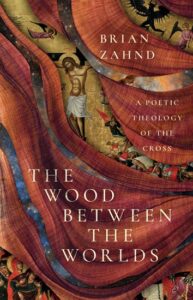

For Christians, the cross may be so familiar that we cease to see it and be shocked by it.

To help us, Bran Zahnd offers an untypical theology of the cross. As the author suggests, The Wood Between the Worlds is an exercise in theopoetics—akin to meditations on nineteen aspects or implications of the death of Christ. Since other excellent volumes cover the standard topics of atonement, substitution, forgiveness, and salvation, Zahnd turns his attention elsewhere.

We read, for example, that while humanity was exiled from Eden and the Tree of Life, now all are welcome at the cross, the true Tree of Life. We also find a profound chapter on Pontius Pilate, and how we are all at some level stained by skepticism and dirty hands. In addition, Zahnd offers a wonderfully clear explanation of Rene Girard’s important work on the social dynamics of scapegoating today and throughout history.

We read, for example, that while humanity was exiled from Eden and the Tree of Life, now all are welcome at the cross, the true Tree of Life. We also find a profound chapter on Pontius Pilate, and how we are all at some level stained by skepticism and dirty hands. In addition, Zahnd offers a wonderfully clear explanation of Rene Girard’s important work on the social dynamics of scapegoating today and throughout history.

Insights and icons from Eastern Orthodox Christianity weave in and out of these and his other uncommon subjects such as Ellie Wiesel’s doubts, the harrowing of hell, and Mary’s ponderings.

Much of the book considers power and weakness. In this light Zahnd takes up uncomfortable topics such as capital punishment, pacifism, and James Cone’s The Cross and the Lynching Tree.

While today’s church often focuses on power, the gospel writers emphasize suffering, loss, and weakness. When Paul says, “God’s weakness is stronger than human strength” (1 Cor 1:25), he “doesn’t mean that when God is weak, God is still stronger than human might. That wouldn’t be scandalous. It would be just a typical boast about power as conventionally understood. Rather Paul is taking us into the deep mystery of the cross, saying that God’s power is precisely located in the weakness” of the cross. [p. 29].

Power corrupts as the Ring of Power in Tolkien’s trilogy twists those who seek it. All our attempts to use power are likewise subject to corruption. Christianity is tainted when it aligns itself with government-sponsored violence as all sides did in World War I and as we still see today. We cannot justify such actions by misunderstanding the imagery of armies and destruction in the book of Revelation. For it is the slain lamb who is the central victor of the book.

Through mystery and metaphor, in this mind-provoking and soul-provoking book, Zahnd explores the literal crux of the Christian story.

Such a story would prove to Nietzsche that he was right, that people don’t operate by ideals, even the most high minded. It’s all a sham, a fake, a charade. Even a political party supposedly built on the foundation of peace with the natural world quickly degenerates into vitriol and violence.

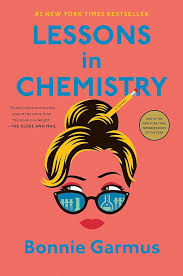

Such a story would prove to Nietzsche that he was right, that people don’t operate by ideals, even the most high minded. It’s all a sham, a fake, a charade. Even a political party supposedly built on the foundation of peace with the natural world quickly degenerates into vitriol and violence. The book highlights the unnecessary limits, the ill treatment, and the stereotypes so many once had and sadly still have of women. But an irony is that the book also seems to perpetuate certain stereotypes.

The book highlights the unnecessary limits, the ill treatment, and the stereotypes so many once had and sadly still have of women. But an irony is that the book also seems to perpetuate certain stereotypes.

Pilate knows just what these leaders are up to when they bring this innocent man to him for judgment, and it isn’t truth. No one wants truth. They just want power.

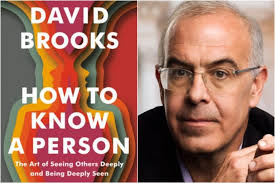

Pilate knows just what these leaders are up to when they bring this innocent man to him for judgment, and it isn’t truth. No one wants truth. They just want power. Having read a half dozen books which tout the significance of and make substantial use of Taylor’s magnum opus,

Having read a half dozen books which tout the significance of and make substantial use of Taylor’s magnum opus,  I could go on for pages about the provocative, game-changing ideas in the book. I haven’t even mentioned his concepts of our disenchanted world and the buffered self which many other books make first-rate use of (such as Alan Noble’s

I could go on for pages about the provocative, game-changing ideas in the book. I haven’t even mentioned his concepts of our disenchanted world and the buffered self which many other books make first-rate use of (such as Alan Noble’s

Some people in this country say our government is so bad it would be better to throw it away and start over. After all, things couldn’t get any worse. If we are tempted this Independence Day to think that we live in bad times, this story reminds us to be grateful for what we have—for things could be worse, much worse.

Some people in this country say our government is so bad it would be better to throw it away and start over. After all, things couldn’t get any worse. If we are tempted this Independence Day to think that we live in bad times, this story reminds us to be grateful for what we have—for things could be worse, much worse.

First, Paul introduces this section on husbands and wives with, “Submit to one another out of reverence for Christ.” Submission for Paul is mutual, not just something a wife offers her husband.

First, Paul introduces this section on husbands and wives with, “Submit to one another out of reverence for Christ.” Submission for Paul is mutual, not just something a wife offers her husband.  Years ago my wife Phyllis felt stunted in her spiritual life by the church we were in. I took that seriously, even though I liked the church. I liked the people. I liked the music. I liked the preaching. It was great for me. After many months of discussion and prayer, however, we were not able to resolve the issue. Then I remembered that Ephesians 5 meant that my wife’s spiritual well-being came before mine. I had to die. So I told her, “It’s up to you. If you want us to go to a different church, we will. I want what’s best for you.”

Years ago my wife Phyllis felt stunted in her spiritual life by the church we were in. I took that seriously, even though I liked the church. I liked the people. I liked the music. I liked the preaching. It was great for me. After many months of discussion and prayer, however, we were not able to resolve the issue. Then I remembered that Ephesians 5 meant that my wife’s spiritual well-being came before mine. I had to die. So I told her, “It’s up to you. If you want us to go to a different church, we will. I want what’s best for you.” Humanity, male and female, is created in God’s image. This is emphasized by repeating it in three slightly different ways. Together we bear God’s image. And what does it mean to do that? The answer is in the very next verse:

Humanity, male and female, is created in God’s image. This is emphasized by repeating it in three slightly different ways. Together we bear God’s image. And what does it mean to do that? The answer is in the very next verse: