“You’re reading a book by him???”

I have friends who don’t tolerate books by people they disagree with. They won’t read them and if they do, they will sharply criticize every aspect. They won’t admit there is anything of value.

This is true of my conservative friends and my liberal friends.

Somehow I am the odd one who likes books I often disagree with. I like books that challenge me and make me think in new ways. I don’t end up agreeing with everything, but I do end up learning something.

I may not think that a Jungian or Marxist or Capitalist framework is the way to view the world as a whole. But when I read books of such persuasions, I am intrigued. Even if I don’t buy it all, I see something that could help as I try to make my way through the world. And I believe it is good for me to nurture empathy for others who have had different experiences.

I try to remember that I don’t know everything, and that the world is big and complex and full of wonder.

Recently I mentioned to a friend a book written by someone whose political ideas she thought were completely wrong. How could I think something like that was a good book? Even though the book itself had nothing to do with politics, she wouldn’t even consider it.

I suggested that liberals can write good books and bad books. Conservatives can also write good books and bad books. I think she understood what I was saying, but I suspect she was still pretty skeptical.

The book I was talking about was interesting, creative, well-written, well-organized, intelligent, and honest. It gave windows of insight into certain aspects of the world I was not previously familiar with. That, I think, is a good book.

Maybe part of the reason I enjoy reading books I disagree with is that I like learning. I find the world endlessly fascinating—whether it be science or history or human nature or an individual’s story. Even if it’s only learning how other people think in ways that I disagree with, it’s still stimulating. I love being a lifelong learner.

It just makes life more interesting.

—

Image by GrumpyBeere from Pixabay

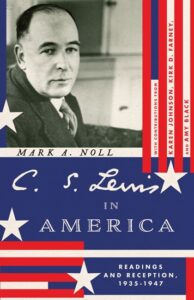

In 1944 Charles Brady wrote a review of Lewis’s output up to that point, including the first installment of Lewis’s Space Trilogy,

In 1944 Charles Brady wrote a review of Lewis’s output up to that point, including the first installment of Lewis’s Space Trilogy,

Anything sound odd to you about that story? Anything odd besides a man being dead in an office for five days without anyone noticing?

Anything sound odd to you about that story? Anything odd besides a man being dead in an office for five days without anyone noticing? That might not even solve all your problems. After all, sending a message into the future can be a tricky business. What could make sure that it didn’t degrade as it passed through the space-time continuum? The technology could break down. Human error or human limitations could prevent the message from being transmitted. And because language and culture change significantly over time, our words and syntax could be difficult to understand by those in the future.

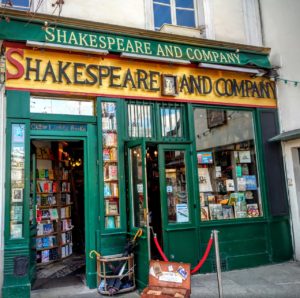

That might not even solve all your problems. After all, sending a message into the future can be a tricky business. What could make sure that it didn’t degrade as it passed through the space-time continuum? The technology could break down. Human error or human limitations could prevent the message from being transmitted. And because language and culture change significantly over time, our words and syntax could be difficult to understand by those in the future. Writing and reading are so commonplace we forget how almost magical the whole process is. We can receive and send ordinary and exceptional stories as well as knowledge across thousands of miles and hundreds of years with people we have never met and who may not know our language.

Writing and reading are so commonplace we forget how almost magical the whole process is. We can receive and send ordinary and exceptional stories as well as knowledge across thousands of miles and hundreds of years with people we have never met and who may not know our language.

Since I tend to like history, science fiction, biblical studies, and literary fiction, I try to get people on my friends list who do too. At the same time, I don’t want my list of friends to be too narrow. I want to be stretched to read in areas I might not ordinarily think of. Sometimes I just want beach reading. So I have friends who read a lot of those. Sometimes I want to read something from a different political or theological perspective. I have friends who point me to those as well.

Since I tend to like history, science fiction, biblical studies, and literary fiction, I try to get people on my friends list who do too. At the same time, I don’t want my list of friends to be too narrow. I want to be stretched to read in areas I might not ordinarily think of. Sometimes I just want beach reading. So I have friends who read a lot of those. Sometimes I want to read something from a different political or theological perspective. I have friends who point me to those as well. Whether due to lack of discipline, lack of focus, or lack of confidence, I only managed to struggle through one chapter. I still remember the look on my teacher’s face and the question when I finished my much truncated report: “Is that all?” Yes, I had to admit, head hung low, that was all.

Whether due to lack of discipline, lack of focus, or lack of confidence, I only managed to struggle through one chapter. I still remember the look on my teacher’s face and the question when I finished my much truncated report: “Is that all?” Yes, I had to admit, head hung low, that was all. Yet one year later, in the summer before high school. I thought it would be a good goal to read

Yet one year later, in the summer before high school. I thought it would be a good goal to read