I was sitting around a table with some friends. How did the topic come up? I don’t quite recall.

We were talking about World War II, and Ralph said, “You can’t trust the Germans. Look what they’ve done in two world wars. And don’t say they’ve changed because skinheads and nationalism are on the rise there. We just should never have let them become an independent nation again. We should have carved up the country for good.”

I was a bit surprised to hear such ideas about a group of people who have little malice thrown at them these days. He didn’t sound angry. He wasn’t loud. He was outwardly calm, but I sensed there was emotion underneath.

I responded evenly by saying it seemed helpful to have them as allies, as a force for economic and political stability in central Europe. Clearly he still disagreed.

Then I remembered what I had just read in David Brooks’s new book, How to Know a Person. He told a story of being on a panel discussion with someone who had a very different view of the culture wars. Brooks responded not with anger or diatribe but by stating his side with a bit of cool dispassion.

Then I remembered what I had just read in David Brooks’s new book, How to Know a Person. He told a story of being on a panel discussion with someone who had a very different view of the culture wars. Brooks responded not with anger or diatribe but by stating his side with a bit of cool dispassion.

Later Brooks realized this was the wrong approach. Instead he should have at least asked more questions about what the other person thought and why.

Taking Brooks’s lead, I decided I too was wrong and that the important thing in this moment was not to try to change Ralph’s mind, not to correct him, however wrong his attitudes might be. My job first was to listen to him, get to know him, and maybe love him a little better.

So I started asking some questions, genuinely wanting to know more: “What’s behind your thoughts here? When and how did you first start to think this way?” And quietly he began to tell us more of his story.

His father and uncles had been in the war. What they saw and went through was terrible. And his wife had been born in central Europe. Her family had suffered at the hands of the Germans for multiple generations.

Ralph was not speculating on geopolitics. For him, this was personal.

Brooks is a consummate journalist who is excellent at summarizing the best research of experts while telling stories of others and himself that move us and create understanding. While offering excellent material on how to get to know people as individuals, he reminds us that everyone is situated in a group, in a history, in a place. We also have to explore and appreciate those to truly hear others.

In a day of hyper reactions and extreme tribalism, we seem to have lost the vital art of conversation, of making friends, of connecting with others more than superficially. Brooks tells us how with practical, sensible wisdom.

I don’t remember the last time I had put the ideas of a book into practice so quickly as I did with Ralph. Before I would have just sat in stunned silence. But now I knew how to respond positively. How to Know a Person is that kind of book, a book worth rereading.

Having read a half dozen books which tout the significance of and make substantial use of Taylor’s magnum opus,

Having read a half dozen books which tout the significance of and make substantial use of Taylor’s magnum opus,  I could go on for pages about the provocative, game-changing ideas in the book. I haven’t even mentioned his concepts of our disenchanted world and the buffered self which many other books make first-rate use of (such as Alan Noble’s

I could go on for pages about the provocative, game-changing ideas in the book. I haven’t even mentioned his concepts of our disenchanted world and the buffered self which many other books make first-rate use of (such as Alan Noble’s

Some people in this country say our government is so bad it would be better to throw it away and start over. After all, things couldn’t get any worse. If we are tempted this Independence Day to think that we live in bad times, this story reminds us to be grateful for what we have—for things could be worse, much worse.

Some people in this country say our government is so bad it would be better to throw it away and start over. After all, things couldn’t get any worse. If we are tempted this Independence Day to think that we live in bad times, this story reminds us to be grateful for what we have—for things could be worse, much worse. I also wrote on how Schaeffer spoke prophetically about one of the most pressing needs that the church has today—showing love to each other. If you’d like to see it, just

I also wrote on how Schaeffer spoke prophetically about one of the most pressing needs that the church has today—showing love to each other. If you’d like to see it, just  Social

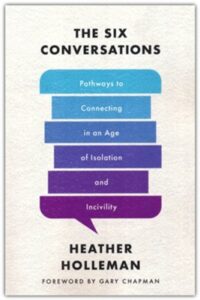

Social To keep great conversations and relationships growing, it’s key to be nonjudgmental, to ask follow-up questions, and not be too quick to give our perspective.

To keep great conversations and relationships growing, it’s key to be nonjudgmental, to ask follow-up questions, and not be too quick to give our perspective.

♦ Reengage with lifelong friends. Admittedly it can be hard to make new friends. An easier but still very fruitful path might be to renew connections with old friends near and far. In recent years I’ve deliberately increased the emails to, calls and zooms with, and visits to several longstanding friends. Some I’ve had spotty contact with over the years, and some I hadn’t seen in decades. But I’ve so enjoyed the results of more regular connection with all of them.

♦ Reengage with lifelong friends. Admittedly it can be hard to make new friends. An easier but still very fruitful path might be to renew connections with old friends near and far. In recent years I’ve deliberately increased the emails to, calls and zooms with, and visits to several longstanding friends. Some I’ve had spotty contact with over the years, and some I hadn’t seen in decades. But I’ve so enjoyed the results of more regular connection with all of them.  In his book

In his book  Grant believes that we will be better off if we think more like scientists (but he’s willing to reconsider!). They actually get excited when they find out they are wrong because this means they may have discovered something new. By realizing they were wrong, scientists in the 20th century alone have discovered vitamins, cosmic rays, insulin, atomic nuclei, the polio vaccine, quasars, and much more.*

Grant believes that we will be better off if we think more like scientists (but he’s willing to reconsider!). They actually get excited when they find out they are wrong because this means they may have discovered something new. By realizing they were wrong, scientists in the 20th century alone have discovered vitamins, cosmic rays, insulin, atomic nuclei, the polio vaccine, quasars, and much more.* The most effective negotiators and debaters, as described by Adam Grant in

The most effective negotiators and debaters, as described by Adam Grant in