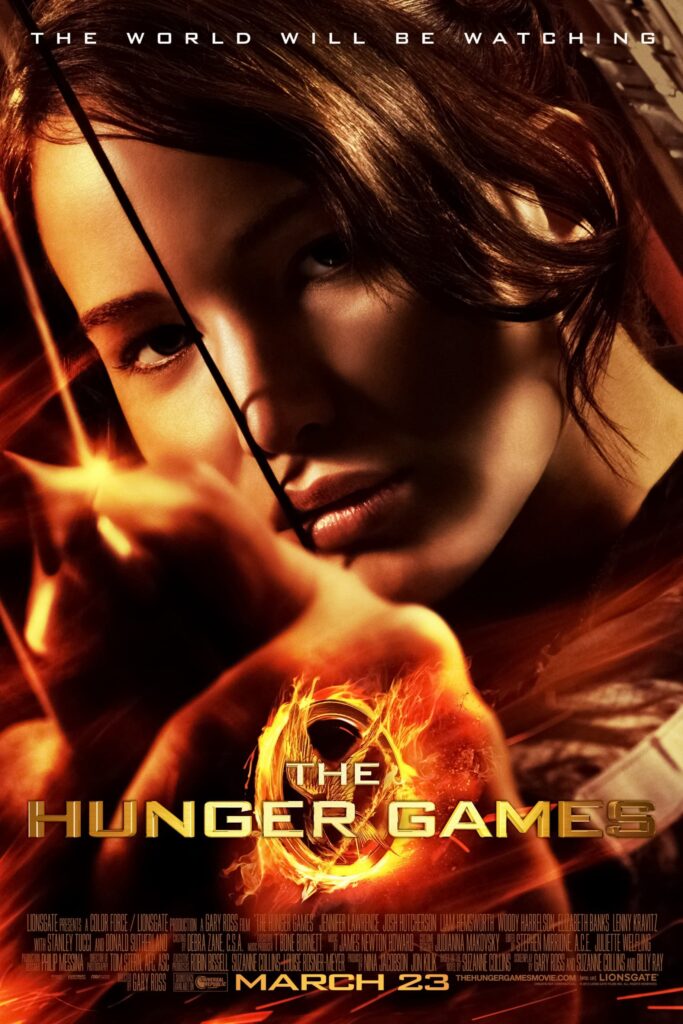

The Hunger Games, The Matrix, Divergent, The Maze Runner, Ready Player One, The Road—these are just a few of the dozens of dystopian movies and novels that have exploded on the scene in the last twenty years.

Books depicting a future that has crumbled into economic, ecological, social, or dictatorial disaster are not entirely new. Jules Verne and H. G. Wells in the nineteenth century offered several versions. Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1936) and George Orwell’s 1984 (1949), however, set the standard for the genre in the last hundred years.

The question I’ve wondered about, however, is why? Why the massive increase in number and popularity? Why all this pessimism? Sarah Irving-Stonebreaker offers one possible explanation.

The Judeo-Christian world view that history is going somewhere, that it has a purpose, has fallen out of favor. Even an atheistic worldview like Marxism which believes that history is headed somewhere—to a workers’ paradise—has also been discredited.

Such positive outlooks have been replaced by a sense that the universe is random and has no purpose. History, therefore, doesn’t matter. “History is not part of any greater story and therefore has little to teach us,” she writes. In fact, our history is merely a source of shame and oppression.* The past cannot and should not tell us who we are, how to act, or where to go.

We are left completely on our own.

While that might seem hopeful to some, it has had the opposite effect. Without a sense of connection to the past and that history is leading us somewhere, all we have left is despair about the future, which is exactly the story that dystopias tell.

Such stories can and do act as cautionary tales. Possibly the first of this genre, Jonathan Swift’s imaginative Gulliver’s Travels (1726) presented a social and political critique of his day. Even the New Testament’s Book of Revelation offers a very dark picture of the future. But it’s purpose is very different than most contemporary apocalyptic visions which may only provide a glimmer of individual hope in the midst of social despair.

Though Revelation may seem confusing, its “main theme is as clear as day: despite present trouble, God is in control, and he will have the final victory. God wins in the end, even though his people at the present live in a toxic culture and are marginalized and even persecuted…. the author’s purpose is to engender hope in the hearts of his Christian readers so that they will have the resolve to withstand the turbulent present.”**

Yes, dystopias can serve a redeeming purpose. But more is needed—the knowledge that we are not alone in our past, in our present, or in our future.

—

*Sarah Irving-Stonebreaker, Priests of History (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2024), 34 and 25-28.

**Tremper Longman III, Revelation Through Old Testament Eyes (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Academic, 2022), 14.