A well-designed page is a joy to the eye and an aid to the brain. We’ve all come across magazines or books or webpages that make reading a chore. Others we may admire for their grace. And some we may not notice at all because their transparency allows the meaning of the text to flow unimpeded, not drawing attention to the design itself.

If you are producing your own book, newsletter, or webpage, don’t skimp on design. It’s worth it to pay someone who knows design to help you. Or invest in a book on page design yourself. At least use a standard template often offered by self-publishing services.

Be alert, however, that not all graphic designers have the same training or experience. Someone expert at magazine covers or web pages may wrongly apply those design principles to a book page. They are not the same. Try to find someone who knows proper proportions for margins, line spacing (or leading), and so forth—for books.

Be alert, however, that not all graphic designers have the same training or experience. Someone expert at magazine covers or web pages may wrongly apply those design principles to a book page. They are not the same. Try to find someone who knows proper proportions for margins, line spacing (or leading), and so forth—for books.

One error amateur and professionals alike can make regards column width. If a column is too wide, the eye gets lost in the middle of the line and readability goes down. If it is too narrow, the eye shifts down too frequently, also hindering comprehension. What’s the happy medium?

For book layout, Simon Garfield offers sound advice in Just My Type: “Readability will be aided by regular paragraphs and sufficient margins, and by an acceptable line length (this is naturally dependent on the size of the text, but is ideally considered to be between ten and twelve words).” (p. 55).

Thus, when using small font (such as 9 pt. or less), don’t have a wide column. Use two or three narrow columns. Or if you have a very wide page, as with a workbook, you can use a larger font, but still, readability requires you use two columns for any lengthy text.

If, however, you intend for users to write in the workbook, a brief question can be a full column (with a somewhat larger font), followed by space for writing. It can also be fine to alternate between (two-column) text-heavy sections and (one-column) for writing out exercises and questions.

Another alternative (especially if you have lots of photos, tables, graphs, and the like) is to have a single column that is at most two-thirds the width of your frame with your graphics going full-frame, as needed.

Design is not an optional extra. Reading is better by design.

—

More Resources

“Line Lengths and Column Widths” from Magazine Design

“Design Options for Self-Publishers” from Publishers Weekly

“6 Keys for Book Page Layout” from TCK Publishing

Graphic Design for Everyone by Cath Caldwell

How do I know?

How do I know?  Here’s how

Here’s how

And how could I have not known that the ampersand (&) is actually an elegant combination of the letters e and t which comprise the Latin word et, meaning “and”? I do now, & am a better person for it.

And how could I have not known that the ampersand (&) is actually an elegant combination of the letters e and t which comprise the Latin word et, meaning “and”? I do now, & am a better person for it. For headlines and huge signs in public places—yes, by all means, give me Helvetica or Univers or Futura. These san serif faces are wonderful, authoritative and to the point. They get me where I want to go whether it is the exit, the entrance, or (most importantly) the men’s room.

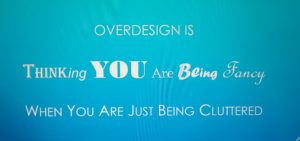

For headlines and huge signs in public places—yes, by all means, give me Helvetica or Univers or Futura. These san serif faces are wonderful, authoritative and to the point. They get me where I want to go whether it is the exit, the entrance, or (most importantly) the men’s room. Having dozens or hundreds of options to choose from was just too much temptation for many. As an editor I often received manuscripts combining a riot of faces and fonts. What authors thought of as fancy or creative was plain distracting and ugly. Our friends at Apple and Microsoft had unleashed the untamed graphic designer in all of us.

Having dozens or hundreds of options to choose from was just too much temptation for many. As an editor I often received manuscripts combining a riot of faces and fonts. What authors thought of as fancy or creative was plain distracting and ugly. Our friends at Apple and Microsoft had unleashed the untamed graphic designer in all of us.