How frustrated are you? Really, how frustrated are you with the culture, the government, the economy, the church, your world, your career, your life? If you are a lot, you are a candidate for becoming a true believer.

In his classic book The True Believer Eric Hoffer unpacks the dynamics of mass movements–who they attract, the phases they go through, the types of leaders they possess, how different groups react, and how they move forward or fail. His working hypothesis is “that the frustrated predominate among the early adherents of all mass movements and that they usually join of their own accord” (p. xii).

They are so dissatisfied with their present world that they are willing to wreck it for only the possibility of a new future. Their dissatisfaction extends to themselves–and as a result they are ready to give themselves over unconditionally to something greater than they are (their party, their nation, their religion, their race). Two generations after Hoffer’s book, J. D. Vance hints at some of these themes in Hillbilly Elegy.

But leaders and followers grow out of somewhat different soils of frustration. Hoffer observes, “Our frustration is greater when we have much and want more than when we have nothing and want some” (p. 29). Thus leaders of mass movements are often people of modest talent who yearn to join the elite but have been shut out.

When I first read this book fifty years ago, I thought it was a book of history about Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini, the French Revolution, the Reformation, the rise of Islam–and so a book about a distant past. On rereading it, the book feels as current as today’s Twitter feed where political and religious true believers so often dominate.

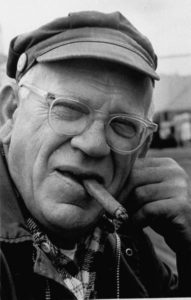

It  is hard to categorize this book. Hoffer, a longshoreman by trade, was called a self-educated philosopher but the book is more one of social and political psychology. He is dense, pithy, provocative, and intensely insightful. Each sentence is like an aphorism that could bloom into a book.

is hard to categorize this book. Hoffer, a longshoreman by trade, was called a self-educated philosopher but the book is more one of social and political psychology. He is dense, pithy, provocative, and intensely insightful. Each sentence is like an aphorism that could bloom into a book.

Consider one example: “Equality without freedom creates a more stable social pattern than freedom without equality” (p. 33).

Or this: “It is the sacred duty of the true believer to be suspicious. He must be constantly on the lookout for saboteurs, spies and traitors” (p. 125).

The True Believer was one of the most important books of the twentieth century. It deserves to be one of the most important of the twenty-first.