After re-reading Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death, I thought about taking a 24-hour fast from media. No TV, no radio, no smart phone, no laptop–for a whole day. Then I remembered it’s winter here in Chicago and weather forecasts are nearly a prerequisite for citizenship. And I’m expecting important emails soon. And what about those text messages I’d miss? And . . .

And I realized that though I think I control my technology, maybe it controls me as much as the next guy.

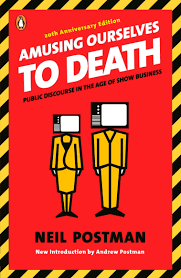

When Postman wrote his book in 1985, Pac-Man was five years old. USA Today was three. The Mac computer was one. Cable TV was in its infancy. Google was twelve years into the future. Netflix wouldn’t open for business for fourteen years. We’d have to wait twenty-two years for the iPhone and Kindle. Despite this or perhaps because of this Amusing Ourselves to Death is a classic that remains as important as ever.

When Postman wrote his book in 1985, Pac-Man was five years old. USA Today was three. The Mac computer was one. Cable TV was in its infancy. Google was twelve years into the future. Netflix wouldn’t open for business for fourteen years. We’d have to wait twenty-two years for the iPhone and Kindle. Despite this or perhaps because of this Amusing Ourselves to Death is a classic that remains as important as ever.

The problem is that such media have created an entertainment culture, and all the new technologies have only reinforced that. What have we lost? The substance of public discourse that a print culture offered us in the previous centuries. Thousands heard Lincoln and Douglas debate in three- and four-hour-long sessions. But it was the dominance of print that made it possible for listeners to be able to follow and to be interested in these events.

Our civic life has been consumed by sound bites and Twitter feeds, reducing millions to passive consumers of media instead of active citizens. Even those outlets that are supposed to provide substance are mostly focused on capturing audiences. MSNBC and FOX have more in common than we think for neither are in the news business. Rather both are trying to make as much money as possible in the entertainment business.

In the introduction for the twentieth-anniversary edition of book, Postman’s son points out that though we are not dominated by network television anymore, the underlying issues of our entertainment-saturated culture remain the same. Has media improved our democracy? Has it made our leaders more accountable? Are we better citizens or are we better consumers? Have our schools improved as a result?

In the introduction for the twentieth-anniversary edition of book, Postman’s son points out that though we are not dominated by network television anymore, the underlying issues of our entertainment-saturated culture remain the same. Has media improved our democracy? Has it made our leaders more accountable? Are we better citizens or are we better consumers? Have our schools improved as a result?

Solutions? Postman admits he has few. Certainly recognizing our disease is a necessary step. Asking questions about media is also needed to break the spell technology has over us. So are periodic fasts such as technology-free family nights once a week or even once a month. We must start somewhere. And reading Postman’s book can be just the place to begin.