The story is classic. The main character enjoys prominence and prestige only to sink into obscurity before slowly rising again. Mark Noll tells this tale in his benchmark book on the history of American evangelical scholarship (1880-1980), Between Faith and Criticism–a book full of insights which still bear fruit today.

Some reasons for the decline are well-known but Noll adds other significant factors. One is the professionalization of academic study beginning in the late nineteenth century. Biblical studies were no longer the exclusive domain of denominational seminaries but became ruled by the technical, research-oriented graduate schools of major universities. In such an environment, assumptions of faith were thought to taint academic pursuits.

Some reasons for the decline are well-known but Noll adds other significant factors. One is the professionalization of academic study beginning in the late nineteenth century. Biblical studies were no longer the exclusive domain of denominational seminaries but became ruled by the technical, research-oriented graduate schools of major universities. In such an environment, assumptions of faith were thought to taint academic pursuits.

Though scholars like A. A. Hodge and B. B. Warfield at Princeton had the stature and substance to maintain some degree of standing in the field, shortly after 1900 such influence hit bottom. The next generation was one of exclusion and retrenchment, highlighted by the writing of The Fundamentals and the highly publicized Scopes Monkey Trial.

The issue which most divided evangelicals from modern or “liberal” scholars and vice versa, was biblical criticism. Noll, assuming his audience knows the term, never defines it (also called higher criticism) which does not mean negative evaluations. Rather it concerns a range of “scientific” approaches (which gained prominence in the nineteenth century) for analyzing texts to determine their meaning and historical accuracy. Many evangelicals objected to conclusions from these methods which included, for example, doubting Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch and assigning a second-century BC date to Daniel. The result, they often felt, called the authority, infallibility, and inerrancy of Scripture into question.

How evangelical scholarship pulled itself out of these doldrums takes us to Britain. First, as members of the established Anglican church, some evangelicals there were always part of the faculty at the elite universities. They were never excluded the way their American counterparts were. Second, through the work of what became Tyndale House and Tyndale Fellowship (both under the umbrella of the InterVarsity Fellowship student ministry), serious scholars and scholarship were nurtured and encouraged. These included F. F. Bruce, G. T. Manley and others.

Via publications and some transatlantic travel both ways, the Brits had a salutary effect on American scholarship. Of ten evangelical commentary series available in the early 1980s, only one had a majority of American contributors.

Via publications and some transatlantic travel both ways, the Brits had a salutary effect on American scholarship. Of ten evangelical commentary series available in the early 1980s, only one had a majority of American contributors.

Noll also offers a taxonomy of evangelical scholarship that is still useful thirty years after his book was published. (1) Critical Anti-Critics “regularly put scholarship to use in defending traditional evangelical beliefs and in attacking the nontraditional conclusions of other scholars.” (2) Believing Critics (led by British scholars) accept that new research may overturn traditional beliefs but that this need not undermine an inspired Bible. They “find insight as well as error in the larger world of biblical scholarship” (p. 158). Generally, then as today, members of the Evangelical Theological Society (ETS) are in the first category while members of the Institute of Biblical Research (IBR) are in the second.

Ultimately, the challenge for evangelicals has been to develop a comprehensive method for understanding both the divine and human aspects of Scripture. Do minor errors or a failure on the part of the biblical writers to (anachronistically) follow 21st-century historiographical conventions call the reliability of the whole Bible into question? Do the fallen and finite human contexts, cultures, and origins of the Scriptures somehow negate their divine inspiration and authority? Or is there a way both can be affirmed? In answering these questions, our British brethren have led and continue to lead the way.

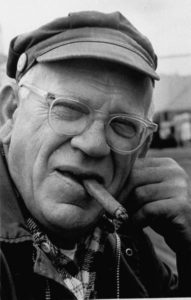

F. F. Bruce photo credit: InterVarsity Press

What of the initial question that inspired the book? He only hints at answers. Certainly the crucified image of the righteous sufferer has remained strong, inspiring many to follow his example even at great risk. Also, it is hard to imagine the Bill of Rights and the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights emerging without the widespread influence of Jesus. “The pressure to make peace [in various quarters of today’s world] is quite unlike anything the Greeks or Romans or even the Elizabethans could have imagined” (310).

What of the initial question that inspired the book? He only hints at answers. Certainly the crucified image of the righteous sufferer has remained strong, inspiring many to follow his example even at great risk. Also, it is hard to imagine the Bill of Rights and the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights emerging without the widespread influence of Jesus. “The pressure to make peace [in various quarters of today’s world] is quite unlike anything the Greeks or Romans or even the Elizabethans could have imagined” (310).

The unwritten agenda of this book and its relevance for today seems to be the similar questions that are now afoot. Does democracy have a future? Can it withstand the impulses of our now hyper technological society joined with the forces of nationalism which once more assert themselves–now in currently democratic societies like Great Britain, India, the United States and elsewhere? What role if any does Christianity have to play other than chaplain to the powers or hand-wringing bystander?

The unwritten agenda of this book and its relevance for today seems to be the similar questions that are now afoot. Does democracy have a future? Can it withstand the impulses of our now hyper technological society joined with the forces of nationalism which once more assert themselves–now in currently democratic societies like Great Britain, India, the United States and elsewhere? What role if any does Christianity have to play other than chaplain to the powers or hand-wringing bystander?

Civil War to end slavery was one such struggle. But the battle continued on new fronts, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries being one of the most obvious. The decades-long, hard fought struggle to gain women the vote in 1920 was another high point except that it took so much effort to achieve what now seems so obvious.

Civil War to end slavery was one such struggle. But the battle continued on new fronts, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries being one of the most obvious. The decades-long, hard fought struggle to gain women the vote in 1920 was another high point except that it took so much effort to achieve what now seems so obvious. is hard to categorize this book. Hoffer, a longshoreman by trade, was called a self-educated philosopher but the book is more one of social and political psychology. He is dense, pithy, provocative, and intensely insightful. Each sentence is like an aphorism that could bloom into a book.

is hard to categorize this book. Hoffer, a longshoreman by trade, was called a self-educated philosopher but the book is more one of social and political psychology. He is dense, pithy, provocative, and intensely insightful. Each sentence is like an aphorism that could bloom into a book.