The story of Christian publishing in the last hundred years is one of spunky start-ups and massive conglomerates, of individual faith and social movements, of passing fads and foundational convictions. It is also a story little told.

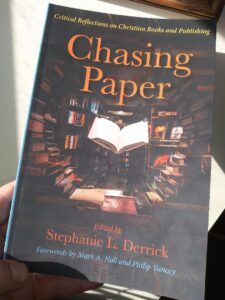

Helping fill that gap is Chasing Paper edited by independent scholar Stephanie Derrick. With forewords by Mark Noll and Philip Yancey as well as twenty brief essays (disclosure: including one I wrote), we hear from key participants whose work helped shape not only their publishing houses but also thousands of books issued in the last sixty years.

Helping fill that gap is Chasing Paper edited by independent scholar Stephanie Derrick. With forewords by Mark Noll and Philip Yancey as well as twenty brief essays (disclosure: including one I wrote), we hear from key participants whose work helped shape not only their publishing houses but also thousands of books issued in the last sixty years.

I was most impressed by the international scope of the collection. The global range of the enterprise is well represented with inside looks at Christian publishing in Brazil, sub-Saharan Africa, Pakistan, the Philippines, Peru, Vatican City, Canada, England, and the United States. The variety of religious communities is also significant, including Catholic as well as Protestant mainline, evangelical, African-American, and Pentecostal.

Most contributors take the approach of memoir, which allows for appropriate storytelling that makes for a quite readable volume. But they do not neglect the social, cultural, economic, and religious context of their work. These broader reflections are illuminating. The authors also relay the specific strategies they employed, strategies which could trigger creative and effective ideas for publishers and authors today who have different contexts with different but similar difficulties.

Peter Dwyer of Liturgical Press, for example, recalled how a dozen years ago he divided the challenges they faced into short-term (the economy of the Great Recession), medium-term (the business model required to deal with e-publishing and Amazon), and long-term (the Catholic Church with its clergy shortage and abuse scandals). Joseph Sinasac’s piece on publishing in Canada also offers a valuable array of strategies for facing the sea changes of recent decades.

Publishers love giving authors an opportunity to tell their stories. Here’s a book that gives publishers a chance to tell their own.

A colleague, Jim Hoover, often said, “An editor is the author’s advocate to the reader—and the reader’s advocate to the author.” The job of editors is not to shape manuscripts the way they would write them. Rather when alerting authors to potential problems, editors aim to show authors what questions people might raise the first time they read the text. That is just virtually impossible for authors to do who are overly familiar with what they’ve written. “Isn’t it obvious?” No. Not always.

A colleague, Jim Hoover, often said, “An editor is the author’s advocate to the reader—and the reader’s advocate to the author.” The job of editors is not to shape manuscripts the way they would write them. Rather when alerting authors to potential problems, editors aim to show authors what questions people might raise the first time they read the text. That is just virtually impossible for authors to do who are overly familiar with what they’ve written. “Isn’t it obvious?” No. Not always.