We all know the story.

Saul persecuted the early Christians until, in a flash of light from the sky, God knocked him off his horse. He heard a voice call to him, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” And who was speaking? “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting.” And that’s how Saul turned from tormenting Jesus Followers to being their foremost missionary.

But there’s one detail in this tale that is wrong. A mistake. The Bible never says it. Yet we have retold this error over and over. What’s amiss?

There was no horse. Acts 9 doesn’t mention it. What about the other two times in Acts that Paul tells his story of meeting Jesus? No horse. Maybe it’s in one of Paul’s letters where he gives a bit of his life story? Sorry. No horse. Even reputable writers like Thomas Cahill perpetuate the myth.*

There was no horse. Acts 9 doesn’t mention it. What about the other two times in Acts that Paul tells his story of meeting Jesus? No horse. Maybe it’s in one of Paul’s letters where he gives a bit of his life story? Sorry. No horse. Even reputable writers like Thomas Cahill perpetuate the myth.*

Why do we keep insisting on a horse? No doubt something is at work here similar to the adage about repeating a lie often enough that it becomes the truth. But there may be another reason. Religious artists over recent centuries have depicted Paul with a four-footed friend, Caravaggio chief among them. So the image fixes itself in our minds.

Admittedly, not much hangs on whether Saul rode a mighty steed or even a bedraggled burro. No decisive doctrine is cast down. No historical record is blinded.

What it does tell us is that we must read the text. And read it carefully. Just because we think the Bible says something, doesn’t make it so. Even if we’ve heard it a hundred times, we need to read slowly, ask good questions, pay attention, write down what we see, be quiet, and listen.

If we do, we might even hear the voice of Jesus.

————–

*Thomas Cahill, Desire of the Everlasting Hills (New York: Doubleday, 1999), p. 123.

Freakonomist Steven Levitt tells us just

Freakonomist Steven Levitt tells us just

Civil War to end slavery was one such struggle. But the battle continued on new fronts, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries being one of the most obvious. The decades-long, hard fought struggle to gain women the vote in 1920 was another high point except that it took so much effort to achieve what now seems so obvious.

Civil War to end slavery was one such struggle. But the battle continued on new fronts, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries being one of the most obvious. The decades-long, hard fought struggle to gain women the vote in 1920 was another high point except that it took so much effort to achieve what now seems so obvious.

is often a dirty word these days. In the book I suggest how this time-honored skill can and should be redeemed and rehabilitated.

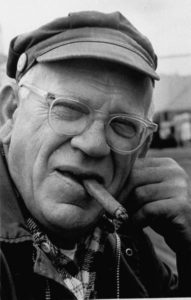

is often a dirty word these days. In the book I suggest how this time-honored skill can and should be redeemed and rehabilitated. is hard to categorize this book. Hoffer, a longshoreman by trade, was called a self-educated philosopher but the book is more one of social and political psychology. He is dense, pithy, provocative, and intensely insightful. Each sentence is like an aphorism that could bloom into a book.

is hard to categorize this book. Hoffer, a longshoreman by trade, was called a self-educated philosopher but the book is more one of social and political psychology. He is dense, pithy, provocative, and intensely insightful. Each sentence is like an aphorism that could bloom into a book.