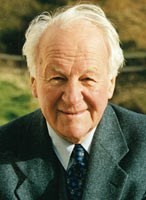

Ten years ago today one of the great Christians of our age passed away. Here is what I posted on that day.

John Stott passed away today at the age of ninety. And it is as if a giant oak of the Christian landscape has fallen. As he has faded from public view in the last few years, some may not appreciate the massive effect this strong, humble leader has had. Not only in his native England, but in North America and across the world his beneficial influence was felt. In Heart. Soul. Mind. Strength. Linda Doll and I looked back on his life’s work in this way:

As 2004 concluded and 2005 began, national recognition came in a variety of high-profile ways to the author who had perhaps defined IVP more than any other over the decades. In the November 30 issue of the New York Times, columnist and commentator David Brooks wrote a stunning op-ed piece on how and why John Stott was the person to listen to from the evangelical fold.

As 2004 concluded and 2005 began, national recognition came in a variety of high-profile ways to the author who had perhaps defined IVP more than any other over the decades. In the November 30 issue of the New York Times, columnist and commentator David Brooks wrote a stunning op-ed piece on how and why John Stott was the person to listen to from the evangelical fold.

He commented, “Falwell and Pat Robertson are held up as spokesmen for evangelicals, which is ridiculous. Meanwhile people like John Stott, who are actually important, get ignored.” He went on to say what it is like to encounter Stott’s books (no doubt many from IVP).

When you read Stott, you encounter first a tone of voice. Tom Wolfe once noticed that at a certain moment all airline pilots came to speak like Chuck Yeager. The parallel is inexact, but over the years I’ve heard hundreds of evangelicals who sound like Stott.

It is a voice that is friendly, courteous and natural. It is humble and self-critical, but also confident, joyful and optimistic. Stott’s mission is to pierce through all the encrustations and share direct contact with Jesus. Stott says that the central message of the gospel is not the teachings of Jesus, but Jesus himself, the human/divine figure. He is always bringing people back to the concrete reality of Jesus’ life and sacrifice.

Shortly afterward, the February 7, 2005, cover story of Time magazine, “The 25 Most Influential Evangelicals in America” also highlighted Stott. He was called quite justifiably “one of the most respected and beloved figures among believers in the U.S. . . . He plunges the rich royalties from his more than 40 unassumingly brilliant books into a fund to educate pastors in the developing word [sic].” (Of course, there is a significant theological difference between the developing word and the developing world. While Time isn’t always known for its theological astuteness, we add sic under the assumption that in this case the usage was inadvertent.)

Only two months later in a special issue featuring “The Time 100,” Time numbered Stott among the one hundred most influential people in the world. The piece on Stott, written by Billy Graham, noted their friendship that began in 1954, Stott’s influence in the Anglican Communion worldwide and his personal humility—his resisting appointment to the position of bishop, the use of his royalties to provide theological books to pastors and scholars in the Two-Thirds World and the simplicity of his living quarters in London’s West End. Graham concluded, “I can’t think of anyone who has been more effective in introducing so many people to a biblical worldview. He represents a touchstone of authentic biblical scholarship that, in my opinion, has scarcely been paralleled since the days of the 16th century European Reformers.”

John Stott was a world Christian before it was fashionable to be a world Christian. On five continents he was known personally and affectionately as Uncle John. Just as he was key to bringing an evangelical renewal to the Church of England, he brought clear, strong teaching and pastoral sensibilities to Latin America, Africa and Asia. Christian leaders all over the world looked to him as their mentor.

The world will miss him.

Once I recall him talking about his concise writing style. “Packer by name; packer by trade,” he responded. I could tell he enjoyed saying that, and I got the impression he used the line often.

Once I recall him talking about his concise writing style. “Packer by name; packer by trade,” he responded. I could tell he enjoyed saying that, and I got the impression he used the line often.  Once several of us took him to lunch, and as we ate IVP publisher Bob Fryling posed the question, “How would you describe IVP among the many Christian publishers that are around?”

Once several of us took him to lunch, and as we ate IVP publisher Bob Fryling posed the question, “How would you describe IVP among the many Christian publishers that are around?”

Such was the power of Coleridge’s personality and intellect that even in the midst of his deep struggles he reshaped the way the world saw Shakespeare in a series of landmark lectures. Previously the Bard was viewed as a second-tier talent of popular leanings. After Coleridge we know him to be the premier wielder of not only the English language but of art and life.

Such was the power of Coleridge’s personality and intellect that even in the midst of his deep struggles he reshaped the way the world saw Shakespeare in a series of landmark lectures. Previously the Bard was viewed as a second-tier talent of popular leanings. After Coleridge we know him to be the premier wielder of not only the English language but of art and life.

Does all this have anything to do with the gospel? Wytsma quotes Timothy Keller: “Any neglect shown to the needs of the members of the vulnerable is not called merely a lack of mercy or charity, but a violation of justice.” Biblical justice is not just punishing evil doers but restoring what was bent or broken. The cross doesn’t just allow sins to be forgiven but restores relationships. It reconciles us to God and us to each other.

Does all this have anything to do with the gospel? Wytsma quotes Timothy Keller: “Any neglect shown to the needs of the members of the vulnerable is not called merely a lack of mercy or charity, but a violation of justice.” Biblical justice is not just punishing evil doers but restoring what was bent or broken. The cross doesn’t just allow sins to be forgiven but restores relationships. It reconciles us to God and us to each other. Lucy Stone launched the women’s rights movement in 1851, inspiring thousands to join the cause for women’s right to vote, work, receive an education, and own property. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were among her early followers. But after years of leading together, in 1869 Anthony and Stanton split from Stone, nearly causing the collapse of the movement. What happened?

Lucy Stone launched the women’s rights movement in 1851, inspiring thousands to join the cause for women’s right to vote, work, receive an education, and own property. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were among her early followers. But after years of leading together, in 1869 Anthony and Stanton split from Stone, nearly causing the collapse of the movement. What happened? Anthony and Stanton were scandalized. But their differences didn’t stop there. “Stone was committed to campaigning at the state level; Anthony and Stanton wanted a federal constitutional amendment. Stone involved men in her organization; Anthony and Stanton favored an exclusively female membership. Stone sought to inspire change through speaking and meetings; Anthony and Stanton were more confrontational, with Anthony voting illegally and encouraging other women to follow suit.” (121)

Anthony and Stanton were scandalized. But their differences didn’t stop there. “Stone was committed to campaigning at the state level; Anthony and Stanton wanted a federal constitutional amendment. Stone involved men in her organization; Anthony and Stanton favored an exclusively female membership. Stone sought to inspire change through speaking and meetings; Anthony and Stanton were more confrontational, with Anthony voting illegally and encouraging other women to follow suit.” (121)

What of the initial question that inspired the book? He only hints at answers. Certainly the crucified image of the righteous sufferer has remained strong, inspiring many to follow his example even at great risk. Also, it is hard to imagine the Bill of Rights and the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights emerging without the widespread influence of Jesus. “The pressure to make peace [in various quarters of today’s world] is quite unlike anything the Greeks or Romans or even the Elizabethans could have imagined” (310).

What of the initial question that inspired the book? He only hints at answers. Certainly the crucified image of the righteous sufferer has remained strong, inspiring many to follow his example even at great risk. Also, it is hard to imagine the Bill of Rights and the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights emerging without the widespread influence of Jesus. “The pressure to make peace [in various quarters of today’s world] is quite unlike anything the Greeks or Romans or even the Elizabethans could have imagined” (310).

The unwritten agenda of this book and its relevance for today seems to be the similar questions that are now afoot. Does democracy have a future? Can it withstand the impulses of our now hyper technological society joined with the forces of nationalism which once more assert themselves–now in currently democratic societies like Great Britain, India, the United States and elsewhere? What role if any does Christianity have to play other than chaplain to the powers or hand-wringing bystander?

The unwritten agenda of this book and its relevance for today seems to be the similar questions that are now afoot. Does democracy have a future? Can it withstand the impulses of our now hyper technological society joined with the forces of nationalism which once more assert themselves–now in currently democratic societies like Great Britain, India, the United States and elsewhere? What role if any does Christianity have to play other than chaplain to the powers or hand-wringing bystander?