In the book of Numbers the people of Israel are judged for moaning and groaning about not having enough food. Then why are there so many Psalms of lament, suggesting that complaining to God is okay?

The answer to this question, that I raised here, begins with understanding the book of Numbers. Though Israel starts with obedience as it prepares for its march into the wilderness (Num 1–10), it quickly slides into rebellion, disobedience, and criticizing God (Num 11–25). The story changes abruptly once the original generation after the Exodus dies in the wilderness (Num 26:63-65). The account of the second generation is then characterized by life and hope (Num 26–36).*

As always, in understanding Scripture, context is foundational. The complaints to God in the book of Numbers were not disconnected incidents which we can treat in isolation. They were part of a pattern, a whole posture of rebellion by the first generation, which God punished them for.

Psalms is a different book with a different context—one aspect of which is that of bringing all our emotions, concerns, praise, frustrations, thanksgiving, and sorrows to God in worship. In fact, more than a third of all psalms are laments, more than any other type of psalm.

Psalms is a different book with a different context—one aspect of which is that of bringing all our emotions, concerns, praise, frustrations, thanksgiving, and sorrows to God in worship. In fact, more than a third of all psalms are laments, more than any other type of psalm.

The book of Psalms suggests that God wants us to engage him fully and honestly as individuals and as a community, with our whole beings—including our griefs and our joys. In this way we are encouraged to hold on tightly to God in the midst our pain and anger rather than to push him away.

Back to the original question. Given what we find in Numbers and the Psalms, is it okay to complain to God? The answer is yes and no. It depends. Is our complaining part of a basic attitude toward God of angry rejection? Or is it part of our pattern of wrestling with God, engaging him deeply and fully?

Our context is crucial as is the context of any given Bible passage. That’s why we can’t treat the Bible as a handbook of quick and easy answers to the complications of life. The Bible was never intended to be a grab bag of independent timeless truths which we can pull out willy-nilly at our whim. We must ponder each episode and comment the way God gave it to us–in the context of the whole.

When two parts of the Bible seem to say opposite things, that doesn’t mean we throw up our hands in despair and conclude that the Bible is not trustworthy. Rather it calls for us to stop, slow down, and meditate on the book as a whole, on the Bible as a whole, and on our life as a whole.

Sometimes complaining will be wrong, Scripture says, and sometimes it won’t. Sometimes it will be hard to tell. In any case God calls us to take the time to ask the Spirit to guide us to discern which is which.

—

*See Dennis T. Olson, “Book of Numbers,” Dictionary of the Old Testament Pentateuch, eds. T. Desmond Alexander and David W. Baker (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2003), pp. 611-18, which summarizes much of what is found in his larger work: Dennis T. Olson, Numbers (IBC; Louisville: Westminster/John Knox, 1996).

Because the New Testament writers were people steeped in the Old Testament, that’s where they often drew ideas, motifs, and references to understand this surprising Jesus who was not the military Messiah they expected. The language of “passing by” recalls the story in Exodus 32–33 when Moses asked God to see his glory. God says, “When my glory passes by, I will put you in a cleft in the rock and cover you with my hand until I have passed by” (Exodus 33:22, my emphasis).

Because the New Testament writers were people steeped in the Old Testament, that’s where they often drew ideas, motifs, and references to understand this surprising Jesus who was not the military Messiah they expected. The language of “passing by” recalls the story in Exodus 32–33 when Moses asked God to see his glory. God says, “When my glory passes by, I will put you in a cleft in the rock and cover you with my hand until I have passed by” (Exodus 33:22, my emphasis).

Chaos dragons are a common image in ancient near eastern literature, and the Bible writers take this and give it several twists for their own purposes. Such dragons often threaten humanity and the whole order God has created. They are associated with the disorder of the sea especially (see my

Chaos dragons are a common image in ancient near eastern literature, and the Bible writers take this and give it several twists for their own purposes. Such dragons often threaten humanity and the whole order God has created. They are associated with the disorder of the sea especially (see my  As Mackie and Collins discuss in their friendly style, these symbols represent a constellation of ideas which consider how dark forces of chaos are not the rival of God but the rival of God’s creation.

As Mackie and Collins discuss in their friendly style, these symbols represent a constellation of ideas which consider how dark forces of chaos are not the rival of God but the rival of God’s creation.

While the differences in Bible versions can be confusing, it’s important to remember the advantages. It means we have a variety of translations well suited for different purposes–some for public reading, some for study, and others for devotional reading. In addition, if we come across phrases like “holy kiss,” “with . . . a double heart,” “make their ears heavy”—we may be left a bit befuddled. By comparing different translations, we can sometimes get a better sense of the range of meanings in a text. 40 Questions charts dozens of translations along a continuum to show how they each wrestle with the balance of accuracy and readability in different ways.

While the differences in Bible versions can be confusing, it’s important to remember the advantages. It means we have a variety of translations well suited for different purposes–some for public reading, some for study, and others for devotional reading. In addition, if we come across phrases like “holy kiss,” “with . . . a double heart,” “make their ears heavy”—we may be left a bit befuddled. By comparing different translations, we can sometimes get a better sense of the range of meanings in a text. 40 Questions charts dozens of translations along a continuum to show how they each wrestle with the balance of accuracy and readability in different ways.

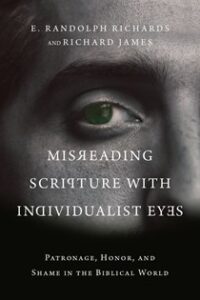

From a Western perspective, we might see patronage as creating unhealthy dependence, even being oppressive. But those inside see it as providing protection, meeting needs, giving security. Yes, it can be abused, but the problem then is not the system but the people in it.

From a Western perspective, we might see patronage as creating unhealthy dependence, even being oppressive. But those inside see it as providing protection, meeting needs, giving security. Yes, it can be abused, but the problem then is not the system but the people in it.

Yet our ruined state need not be permanent. Isaiah also tells us this condition will be reversed. A day is coming when “the deaf will hear the words of the scroll, and out of gloom and darkness the eyes of the blind will see” (Is 29:18). This theme is echoed through the New Testament as well. Yes, the punishment is intentional but not eternal. Its purpose is to get the attention of sinners so they do turn to God.

Yet our ruined state need not be permanent. Isaiah also tells us this condition will be reversed. A day is coming when “the deaf will hear the words of the scroll, and out of gloom and darkness the eyes of the blind will see” (Is 29:18). This theme is echoed through the New Testament as well. Yes, the punishment is intentional but not eternal. Its purpose is to get the attention of sinners so they do turn to God.