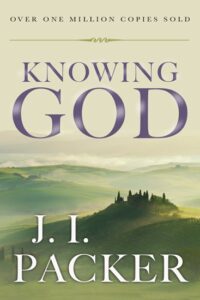

Over my forty years at InterVarsity Press I crossed paths with J. I. Packer a number of times. This soft-spoken and steady British theologian, who died this past week, became something of an accidental celebrity when his substantive book Knowing God suddenly became a best seller. When, as a newly minted InterVarsity campus staff member in 1973, I learned that IVP sometimes gave free books to staff, I made sure they knew that’s the book I wanted. I drank it in.

Once I recall him talking about his concise writing style. “Packer by name; packer by trade,” he responded. I could tell he enjoyed saying that, and I got the impression he used the line often.

Once I recall him talking about his concise writing style. “Packer by name; packer by trade,” he responded. I could tell he enjoyed saying that, and I got the impression he used the line often.

On another occasion Jim reprimanded me and IVP for dropping the dedication to his wife in our latest printing of Knowing God. I assured him that wasn’t possible. He assured me it was. He was right. I checked, and somehow it had been dropped. We fixed it next printing.

I introduced him two times when he was a speaker, and once ran him on an errand for cookies for the group of Regent students he was hosting. I was impressed by how he took personal responsibility to make sure his students were treated with genuine hospitality.

Once several of us took him to lunch, and as we ate IVP publisher Bob Fryling posed the question, “How would you describe IVP among the many Christian publishers that are around?”

Once several of us took him to lunch, and as we ate IVP publisher Bob Fryling posed the question, “How would you describe IVP among the many Christian publishers that are around?”

Immediately Jim responded, “Some publishers tell you what you should believe. Other publishers tell you what you already believe. But IVP helps you to believe.” We were amazed at the instantaneous response, but he took it as par for the course that he could spout off such aphorisms on demand, and gladly gave us permission to use the line publicly.

Perhaps my most memorable encounter was when I got a glimpse into his humanity. At a conference I was assigned the task of chauffeuring him and another famous author. As these two good friends talked in the back seat, they began sharing intimate updates on their similar experiences of grief and difficulty—all as if I were not there. I never forgot that no matter how elevated we might be, we are not immune to life.

And I never forgot the joy and good humor Jim always exhibited in every circumstance.

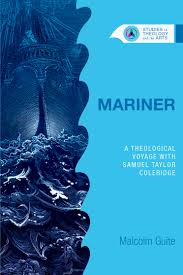

Such was the power of Coleridge’s personality and intellect that even in the midst of his deep struggles he reshaped the way the world saw Shakespeare in a series of landmark lectures. Previously the Bard was viewed as a second-tier talent of popular leanings. After Coleridge we know him to be the premier wielder of not only the English language but of art and life.

Such was the power of Coleridge’s personality and intellect that even in the midst of his deep struggles he reshaped the way the world saw Shakespeare in a series of landmark lectures. Previously the Bard was viewed as a second-tier talent of popular leanings. After Coleridge we know him to be the premier wielder of not only the English language but of art and life.  You can probably rewrite 90% of these sentences in active voice. For example,

You can probably rewrite 90% of these sentences in active voice. For example, Weak: The reason is because Facebook is trying to suck all the DNA out of my body.

Weak: The reason is because Facebook is trying to suck all the DNA out of my body.

Since I tend to like history, science fiction, biblical studies, and literary fiction, I try to get people on my friends list who do too. At the same time, I don’t want my list of friends to be too narrow. I want to be stretched to read in areas I might not ordinarily think of. Sometimes I just want beach reading. So I have friends who read a lot of those. Sometimes I want to read something from a different political or theological perspective. I have friends who point me to those as well.

Since I tend to like history, science fiction, biblical studies, and literary fiction, I try to get people on my friends list who do too. At the same time, I don’t want my list of friends to be too narrow. I want to be stretched to read in areas I might not ordinarily think of. Sometimes I just want beach reading. So I have friends who read a lot of those. Sometimes I want to read something from a different political or theological perspective. I have friends who point me to those as well.

Does all this have anything to do with the gospel? Wytsma quotes Timothy Keller: “Any neglect shown to the needs of the members of the vulnerable is not called merely a lack of mercy or charity, but a violation of justice.” Biblical justice is not just punishing evil doers but restoring what was bent or broken. The cross doesn’t just allow sins to be forgiven but restores relationships. It reconciles us to God and us to each other.

Does all this have anything to do with the gospel? Wytsma quotes Timothy Keller: “Any neglect shown to the needs of the members of the vulnerable is not called merely a lack of mercy or charity, but a violation of justice.” Biblical justice is not just punishing evil doers but restoring what was bent or broken. The cross doesn’t just allow sins to be forgiven but restores relationships. It reconciles us to God and us to each other.

God’s glory gets particular emphasis in this book. As the author says in his discussion of Romans 4:20-21, “Genuine faith in God magnifies his worth. By faith, we honor him” (48). In this vein Romans often focuses on how God deals with Jews and non-Jews, bringing them both into his family, to glorify him. A Jewish sense of superiority relegates God to a tribal deity. Therefore, “Romans contradicts the idea that ethnic conflict is a second-tier concern for the church” (65).

God’s glory gets particular emphasis in this book. As the author says in his discussion of Romans 4:20-21, “Genuine faith in God magnifies his worth. By faith, we honor him” (48). In this vein Romans often focuses on how God deals with Jews and non-Jews, bringing them both into his family, to glorify him. A Jewish sense of superiority relegates God to a tribal deity. Therefore, “Romans contradicts the idea that ethnic conflict is a second-tier concern for the church” (65). How do I know?

How do I know?  Here’s how

Here’s how

And how could I have not known that the ampersand (&) is actually an elegant combination of the letters e and t which comprise the Latin word et, meaning “and”? I do now, & am a better person for it.

And how could I have not known that the ampersand (&) is actually an elegant combination of the letters e and t which comprise the Latin word et, meaning “and”? I do now, & am a better person for it. For headlines and huge signs in public places—yes, by all means, give me Helvetica or Univers or Futura. These san serif faces are wonderful, authoritative and to the point. They get me where I want to go whether it is the exit, the entrance, or (most importantly) the men’s room.

For headlines and huge signs in public places—yes, by all means, give me Helvetica or Univers or Futura. These san serif faces are wonderful, authoritative and to the point. They get me where I want to go whether it is the exit, the entrance, or (most importantly) the men’s room. Having dozens or hundreds of options to choose from was just too much temptation for many. As an editor I often received manuscripts combining a riot of faces and fonts. What authors thought of as fancy or creative was plain distracting and ugly. Our friends at Apple and Microsoft had unleashed the untamed graphic designer in all of us.

Having dozens or hundreds of options to choose from was just too much temptation for many. As an editor I often received manuscripts combining a riot of faces and fonts. What authors thought of as fancy or creative was plain distracting and ugly. Our friends at Apple and Microsoft had unleashed the untamed graphic designer in all of us.

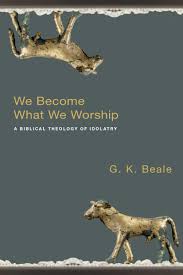

Yet our ruined state need not be permanent. Isaiah also tells us this condition will be reversed. A day is coming when “the deaf will hear the words of the scroll, and out of gloom and darkness the eyes of the blind will see” (Is 29:18). This theme is echoed through the New Testament as well. Yes, the punishment is intentional but not eternal. Its purpose is to get the attention of sinners so they do turn to God.

Yet our ruined state need not be permanent. Isaiah also tells us this condition will be reversed. A day is coming when “the deaf will hear the words of the scroll, and out of gloom and darkness the eyes of the blind will see” (Is 29:18). This theme is echoed through the New Testament as well. Yes, the punishment is intentional but not eternal. Its purpose is to get the attention of sinners so they do turn to God.