My brother-in-law was fond of saying with a wry grin, “Wives are supposed to submit with joy, and husbands are supposed to . . . er, are supposed to . . . um, I always forget that part!”

Many have tripped over what the apostle Paul says in his infamous passage about marriage. That’s the one in his letter to the Ephesians where he talks about submission. What he actually says, though, may surprise some–including my brother-in-law.

First, Paul introduces this section on husbands and wives with, “Submit to one another out of reverence for Christ.” Submission for Paul is mutual, not just something a wife offers her husband.

First, Paul introduces this section on husbands and wives with, “Submit to one another out of reverence for Christ.” Submission for Paul is mutual, not just something a wife offers her husband.

This is consistent with his whole letter which tells us that unity, oneness in Christ, summarizes the whole purpose and aims of God (Eph 1:9-10). One particular example of this is the unity that different groups of people, Jews and Gentiles in this case, were to have in Christ (Eph 2:14; 3:6). In fact such oneness is the key evidence for the principalities and powers that they are no longer in charge but that God is instead (Eph 3:10-11).

The next three chapters are about how this unity is to be maintained (Eph 4:2-3). Humility, gentleness, patience, and love are to characterize how all Christians relate to all other Christians. Pride, harshness, and domination are not how Jews and Gentiles, or men and women, should relate to each other.

Second, when it comes to Paul’s specific instructions, note that he addresses wives and husbands separately (Eph 5:22-24 and 25-33). What’s the significance of this? For one, Paul never says, “Husbands, make sure your wives submit!” The instruction is to wives, not husbands. It’s an issue between a wife and her Lord. Husbands need to leave Ephesians 5:22-24 to their wives and not use it as a weapon in their relationship. The same is true for wives regarding 5:25-33.

Third, Paul devotes three verse to wives but nine verse to husbands—three times as much. Why? In the typically patriarchal culture of Paul’s day, what he says to wives may not sound that new except for the key point he emphasizes—the motivation and means for being a wife is centered on Christ.

Everything Paul says to husbands, however, is very different from what they would have heard from their society. So Paul needs extra time to impress these differences on them. And what does Paul say?

He says husbands are to love their wives “just as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her.” Husbands are to die—like Jesus. Christ sacrificed his life, set aside his status and authority, so the church could flourish in holiness and union with God (Eph 5:25-27). The main job of a husband is not to rule, not to command, not to decide, but to die. If his career goals get in the way of the good of his wife, his ambitions must die. If the part of the country he wants to live in gets in the way of his wife flourishing in Christ, that must die.

Years ago my wife Phyllis felt stunted in her spiritual life by the church we were in. I took that seriously, even though I liked the church. I liked the people. I liked the music. I liked the preaching. It was great for me. After many months of discussion and prayer, however, we were not able to resolve the issue. Then I remembered that Ephesians 5 meant that my wife’s spiritual well-being came before mine. I had to die. So I told her, “It’s up to you. If you want us to go to a different church, we will. I want what’s best for you.”

Years ago my wife Phyllis felt stunted in her spiritual life by the church we were in. I took that seriously, even though I liked the church. I liked the people. I liked the music. I liked the preaching. It was great for me. After many months of discussion and prayer, however, we were not able to resolve the issue. Then I remembered that Ephesians 5 meant that my wife’s spiritual well-being came before mine. I had to die. So I told her, “It’s up to you. If you want us to go to a different church, we will. I want what’s best for you.”

The primary job of a husband is not to make sure his wife stays in her lane. Rather, if she has gifts in hospitality, generosity, leadership, evangelism, compassion, teaching, getting people organized, or more, my role is to support, encourage, and pave the way for her. After all, as Genesis 1:28 says, God’s design for men and women is to rule the created order together as God’s representatives.

My parents had a tremendously positive influence on me by modeling a marriage of true partnership. But throughout the five decades of my own marriage, Ephesians 5 had more. My love for Phyllis focused me on making sure she had every opportunity to grow closer to God and use all the many gifts God gave her.

Now if you are very good and very quiet and if you listen very carefully, in my next time installment I will tell you a story full of twists and turns, pathos and poetry (not to mention uproarious surprises) in which Andy tries to do something good for Phyllis, and she just won’t cooperate.

—

Image: Wedding rings by Arek Socha from Pixabay

Image: Church from Immanuel Presbyterian Church, Warrenville, IL.

First, Paul introduces this section on husbands and wives with, “Submit to one another out of reverence for Christ.” Submission for Paul is mutual, not just something a wife offers her husband.

First, Paul introduces this section on husbands and wives with, “Submit to one another out of reverence for Christ.” Submission for Paul is mutual, not just something a wife offers her husband.  Years ago my wife Phyllis felt stunted in her spiritual life by the church we were in. I took that seriously, even though I liked the church. I liked the people. I liked the music. I liked the preaching. It was great for me. After many months of discussion and prayer, however, we were not able to resolve the issue. Then I remembered that Ephesians 5 meant that my wife’s spiritual well-being came before mine. I had to die. So I told her, “It’s up to you. If you want us to go to a different church, we will. I want what’s best for you.”

Years ago my wife Phyllis felt stunted in her spiritual life by the church we were in. I took that seriously, even though I liked the church. I liked the people. I liked the music. I liked the preaching. It was great for me. After many months of discussion and prayer, however, we were not able to resolve the issue. Then I remembered that Ephesians 5 meant that my wife’s spiritual well-being came before mine. I had to die. So I told her, “It’s up to you. If you want us to go to a different church, we will. I want what’s best for you.” Humanity, male and female, is created in God’s image. This is emphasized by repeating it in three slightly different ways. Together we bear God’s image. And what does it mean to do that? The answer is in the very next verse:

Humanity, male and female, is created in God’s image. This is emphasized by repeating it in three slightly different ways. Together we bear God’s image. And what does it mean to do that? The answer is in the very next verse: But there’s something else you should know about my dad. He was a confirmed bachelor for forty-six years. He had decided he would not get married because he had never seen a happily married couple. And as he told us, the reason for the unhappiness was always money.

But there’s something else you should know about my dad. He was a confirmed bachelor for forty-six years. He had decided he would not get married because he had never seen a happily married couple. And as he told us, the reason for the unhappiness was always money.  Extravagance wasn’t the lesson I got from this episode or from watching my parents for decades. After all, they had both lived through the Depression, and frugality was baked into my DNA.

Extravagance wasn’t the lesson I got from this episode or from watching my parents for decades. After all, they had both lived through the Depression, and frugality was baked into my DNA.  I also wrote on how Schaeffer spoke prophetically about one of the most pressing needs that the church has today—showing love to each other. If you’d like to see it, just

I also wrote on how Schaeffer spoke prophetically about one of the most pressing needs that the church has today—showing love to each other. If you’d like to see it, just  Social

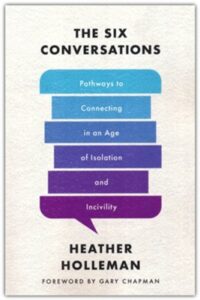

Social To keep great conversations and relationships growing, it’s key to be nonjudgmental, to ask follow-up questions, and not be too quick to give our perspective.

To keep great conversations and relationships growing, it’s key to be nonjudgmental, to ask follow-up questions, and not be too quick to give our perspective.

♦ Reengage with lifelong friends. Admittedly it can be hard to make new friends. An easier but still very fruitful path might be to renew connections with old friends near and far. In recent years I’ve deliberately increased the emails to, calls and zooms with, and visits to several longstanding friends. Some I’ve had spotty contact with over the years, and some I hadn’t seen in decades. But I’ve so enjoyed the results of more regular connection with all of them.

♦ Reengage with lifelong friends. Admittedly it can be hard to make new friends. An easier but still very fruitful path might be to renew connections with old friends near and far. In recent years I’ve deliberately increased the emails to, calls and zooms with, and visits to several longstanding friends. Some I’ve had spotty contact with over the years, and some I hadn’t seen in decades. But I’ve so enjoyed the results of more regular connection with all of them.  In his book

In his book  Grant believes that we will be better off if we think more like scientists (but he’s willing to reconsider!). They actually get excited when they find out they are wrong because this means they may have discovered something new. By realizing they were wrong, scientists in the 20th century alone have discovered vitamins, cosmic rays, insulin, atomic nuclei, the polio vaccine, quasars, and much more.*

Grant believes that we will be better off if we think more like scientists (but he’s willing to reconsider!). They actually get excited when they find out they are wrong because this means they may have discovered something new. By realizing they were wrong, scientists in the 20th century alone have discovered vitamins, cosmic rays, insulin, atomic nuclei, the polio vaccine, quasars, and much more.*