Interpreting the Old Testament can be a tricky business. What do we do with all those laws in Leviticus? Do the promises to Israel apply to us or the church, or neither? And those prophecies in Daniel—they are pretty weird. The author of Ecclesiastes also seems kind of depressed. Does he need cheering up?

In Wisdom for Faithful Reading, John Walton (author of the stellar volume The Lost World of Genesis One) offers much helpful advice on how to keep going off the rails into fanciful interpretations of prophecy and unwarranted applications of narratives. His valuable principles include:

♦ Stay close to the biblical author’s intentions and purposes

♦ Consider closely the linguistic, literary, cultural, and theological context of each passage

♦ Don’t impose our modern ideas, context, or worldview on a text

♦ Remember that genre (whether poetry, prophecy, genealogies, narrative, wisdom literature) is key to understanding

♦ Avoid reading the Bible as a how-to book or an instruction manual

♦ Keep asking this main question about each passage: “What can we learn about God, his plans, and his purposes?”

At each point, Walton offers many concrete examples from all over the Old Testament that illustrate and illuminate each point.

His examples of correct interpretation, however, may reveal a problem for many readers. While his analysis in each sample text is insightful and helpful, he gives the impression that if you don’t know Greek and Hebrew as well as he does, and if you aren’t thoroughly trained in ancient Middle Eastern culture and customs as he is, you can’t possibly understand the Bible. Though he tries to address that, overall it can be discouraging for ordinary readers.

His examples of correct interpretation, however, may reveal a problem for many readers. While his analysis in each sample text is insightful and helpful, he gives the impression that if you don’t know Greek and Hebrew as well as he does, and if you aren’t thoroughly trained in ancient Middle Eastern culture and customs as he is, you can’t possibly understand the Bible. Though he tries to address that, overall it can be discouraging for ordinary readers.

Sometimes he also seems to strip the Bible of its authority rather than highlight it. For example, according to Walton, anything that is common knowledge in the ancient world (like it is bad to steal or murder) would not count as revelation. Only why the author included the Ten Commandments is revelation (pp. 40-47 and 115-16).

I also have questions about the primary mantra he keeps repeating throughout the book: “Only the author’s intentions carry authority.” That is, if the original biblical author never consciously intended a certain meaning, then that cannot possibly be normative for us today. I see at least three problems.

First, for centuries the primary (not the only) way in which the early church fathers interpreted the Old Testament, was to see Christ in every page. And if Jesus is the same as the God of the Old Testament, then there is merit in that approach. Walton would seem to dismiss this out of hand because the ancient writers couldn’t possibly know anything about Jesus, and so he couldn’t be part of their literary intent. Though it is true we must also view the Old Testament on its own terms, I think we dare not shed the perspective of our early Christian heritage lightly.

Second, all authors (biblical or not) communicate things that were not part of their original, conscious message. Yet these are every bit as much a part of the actual communication as that which was consciously intended. The Old Testament authors were thoroughly immersed in the ancient writings that had come before them. The prophets and psalmists knew the Torah deeply. Were they always conscious of when and how it was influencing them? No, but it did. Likewise, are we conscious how assumptions about democracy, individual freedom, capitalism, and (even) Shakespeare are influencing us when we write? No. But these are deep and real influences that emerge in our writing all the time, even when we do not consciously intend them to come out.

Third, I wonder if Walton’s laser-like focus on author intent doesn’t contradict one of his own principles—don’t impose “a foreign perspective on the text.” Isn’t the principle of author intent a modern construct which might get in the way of our encounter with Scripture? Until the last century or so, has anyone in the history of interpretation had such a single-minded obsession with this principle? Doesn’t it largely come out of modern literary theory rather than from the world of the Bible itself?

In this book Walton is legitimately reacting to the many abuses of interpretation that have sadly wracked the church, especially in modern times. The guards he offers to protect against these missteps have much to commend them. But I fear that instead of just reacting to these problems, that he is overreacting.

Having said that, his very last chapter, “Living Life in Light of Scripture,” is a wonderful, clear-headed, positive statement of what we should be looking for from God and his Word. We would all do well to follow Walton’s encouragement to focus on the message of the Bible to trust God, love God, and love others regardless of what life may bring.

Twenty-five years ago, Christine Pohl wrote, “News reports and documentaries broadcast the most terrible details of the lives of refugees or famine victims thousands of miles away, and regularly bring their faces and stories into the most intimate spaces of our homes.”

Twenty-five years ago, Christine Pohl wrote, “News reports and documentaries broadcast the most terrible details of the lives of refugees or famine victims thousands of miles away, and regularly bring their faces and stories into the most intimate spaces of our homes.” But then how would I know where to contribute when a crisis arises? Simply by giving to a relief organization you trust on a regular basis, regardless of whether or not there is a special need. Such crises, sadly, happen often. Send your gift to someone like the Red Cross, World Relief, Doctors Without Borders, or World Vision and designate it to “where needed most.”

But then how would I know where to contribute when a crisis arises? Simply by giving to a relief organization you trust on a regular basis, regardless of whether or not there is a special need. Such crises, sadly, happen often. Send your gift to someone like the Red Cross, World Relief, Doctors Without Borders, or World Vision and designate it to “where needed most.”

With the blizzard still raging, our car was eventually able to limp to a nearby exit for a small town where Phyllis and I sheltered in a restaurant with our four young children, all of us dazed and uncertain what to do. As we were standing there among dozens of other stranded motorists, we heard rumors that the town was going to open up the local high school gym so people would have a place to stay that cold winter night.

With the blizzard still raging, our car was eventually able to limp to a nearby exit for a small town where Phyllis and I sheltered in a restaurant with our four young children, all of us dazed and uncertain what to do. As we were standing there among dozens of other stranded motorists, we heard rumors that the town was going to open up the local high school gym so people would have a place to stay that cold winter night. I could hardly believe it. We were the ones in need. We were the ones who had been helped, but somehow they were the ones who were blessed.

I could hardly believe it. We were the ones in need. We were the ones who had been helped, but somehow they were the ones who were blessed. Instead of splitting the atom (the fission technology that makes nuclear bombs possible), “

Instead of splitting the atom (the fission technology that makes nuclear bombs possible), “

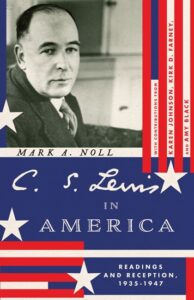

In 1944 Charles Brady wrote a review of Lewis’s output up to that point, including the first installment of Lewis’s Space Trilogy,

In 1944 Charles Brady wrote a review of Lewis’s output up to that point, including the first installment of Lewis’s Space Trilogy,

Chaos dragons are a common image in ancient near eastern literature, and the Bible writers take this and give it several twists for their own purposes. Such dragons often threaten humanity and the whole order God has created. They are associated with the disorder of the sea especially (see my

Chaos dragons are a common image in ancient near eastern literature, and the Bible writers take this and give it several twists for their own purposes. Such dragons often threaten humanity and the whole order God has created. They are associated with the disorder of the sea especially (see my  As Mackie and Collins discuss in their friendly style, these symbols represent a constellation of ideas which consider how dark forces of chaos are not the rival of God but the rival of God’s creation.

As Mackie and Collins discuss in their friendly style, these symbols represent a constellation of ideas which consider how dark forces of chaos are not the rival of God but the rival of God’s creation.

Phyllis didn’t show her concern only when people were overtly hurting. She took delight in getting to know everyone she encountered—on a bus, standing in line, sitting in a park. Because of her genuine interest and ready laugh, they were quite willing to engage her in conversation. People just felt better about life and themselves after being with Phyllis.

Phyllis didn’t show her concern only when people were overtly hurting. She took delight in getting to know everyone she encountered—on a bus, standing in line, sitting in a park. Because of her genuine interest and ready laugh, they were quite willing to engage her in conversation. People just felt better about life and themselves after being with Phyllis. In addition, she began giving more focused attention to an elderly widow who lived on our block. She played board games with her and brought over meals once a week or more.

In addition, she began giving more focused attention to an elderly widow who lived on our block. She played board games with her and brought over meals once a week or more. That can sound eerily like many people today who only associate with those who share their political viewpoints and who only consume “news” from outlets (right or left) that they agree with. They may be unwittingly cooperating with their own mental and emotional exploitation.

That can sound eerily like many people today who only associate with those who share their political viewpoints and who only consume “news” from outlets (right or left) that they agree with. They may be unwittingly cooperating with their own mental and emotional exploitation.  Instead The Persuaders reports on some of the different approaches left-leaning strategists, activists, and legislators have been using recently to shift the thinking of voters. Each chapter focuses on one or two key people, such as Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and others. And we find some interesting approaches described which depart from less than successful practices of the past.

Instead The Persuaders reports on some of the different approaches left-leaning strategists, activists, and legislators have been using recently to shift the thinking of voters. Each chapter focuses on one or two key people, such as Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and others. And we find some interesting approaches described which depart from less than successful practices of the past.  Often I am annoyed by reviews that say, I don’t like this book because the author didn’t write it the way I would have. And there may be some of that in my critique. But the book could have been so much better (more persuasive?) if the author had taken longer to write it, thought more deeply about the nature of persuasion, and guided us more concretely on how the character of our national discussions needs to change to preserve and enhance civility and democracy.

Often I am annoyed by reviews that say, I don’t like this book because the author didn’t write it the way I would have. And there may be some of that in my critique. But the book could have been so much better (more persuasive?) if the author had taken longer to write it, thought more deeply about the nature of persuasion, and guided us more concretely on how the character of our national discussions needs to change to preserve and enhance civility and democracy.

Miller argues that nationalism does not create national unity, as its proponents contend. Rather Christian nationalism still has anti-democratic, illiberal tendencies, especially in how it treats ethnic and religious minorities. “Nationalism is the identity politics of the majority tribe. . . . It perpetuates the cycle of political warfare between nationalist majorities and identity-group minorities, each side . . . trying to seize state power and milk it for perks for their tribe” (p. 108).

Miller argues that nationalism does not create national unity, as its proponents contend. Rather Christian nationalism still has anti-democratic, illiberal tendencies, especially in how it treats ethnic and religious minorities. “Nationalism is the identity politics of the majority tribe. . . . It perpetuates the cycle of political warfare between nationalist majorities and identity-group minorities, each side . . . trying to seize state power and milk it for perks for their tribe” (p. 108).