Complaining about political gridlock is our new national pastime. Congress seems to get barely anything done. What would the Founding Fathers of the United States think about all this? They’d be delighted.

Why? Because it would mean that the Constitution was working as intended—making change difficult and slow.

How did they achieve this? By spreading out power among various groups nationally (the executive, legislative, and judicial branches) and sharing it with the states (which have their own executive, legislative and judicial branches, as well as city and county divisions). We call this a system of checks and balances, and separation of powers. The intentional result, sometimes, is gridlock.

Why did they do this? Because they didn’t trust human nature.

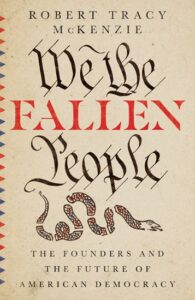

In this first of a series of posts, I will unpack this story and several others told by Robert Tracy McKenzie in We the Fallen People, one of the most important, insightful, and worthwhile books of recent years. This vital work not only gives us some fascinating history but also offers key observations and wisdom for our own day.

In this first of a series of posts, I will unpack this story and several others told by Robert Tracy McKenzie in We the Fallen People, one of the most important, insightful, and worthwhile books of recent years. This vital work not only gives us some fascinating history but also offers key observations and wisdom for our own day.

So why didn’t the Founders trust human nature? “The problem as they understood it,” McKenzie writes, “is not that we’re wholly evil; it’s that we’re not reliably good” (p. 17). “The Founders were realists. They exhorted Americans to revere and practice virtue. They didn’t expect it” (p. 42).

Checks and balances are especially important because they didn’t want one person or group to be easily able to impose its will on others. While they rejected the potential tyranny of king, they also rejected the potential tyranny of the majority—even a majority of white males who were the only ones who could vote.

Hamilton observed that “this is why we have government in the first place: ‘because the passions of men will not conform to the dictates of reason and justice without constraint’” (p. 54).

The Founders were not perfect themselves in avoiding this problem—witness the tyranny of the majority of white males over slaves and Native Americans, and the absence of political representation by white women.

It may sound strange that they distrusted democracy, but it explains why originally the Constitution called for senators to be elected indirectly by the state legislators. It’s also why they didn’t want the President elected directly but through the Electoral College.

It may sound strange that they distrusted democracy, but it explains why originally the Constitution called for senators to be elected indirectly by the state legislators. It’s also why they didn’t want the President elected directly but through the Electoral College.

How things have changed! Today most Americans as well as most Christians (according to polls) reject the underlying assumption of the Founders that human nature is driven by self-interest, often at the expense of others. We the people now believe in the goodness of human nature—at least the goodness of American human nature. And if not that, then at least the goodness of those we agree with!

We the people have no doubts about how good and noble and true are our opinions, our motivations, and our goals. The Founders believed we should be very suspect of exactly these things, and they built that understanding into the Constitution.

Remarkably, the shift about human nature from the realism of the Founders to the optimism of today did not begin with Oprah Winfrey or Thomas Harris’s 1960s bestseller I’m OK—You’re OK or Norman Vincent Peale’s radio show from the 1930s and his The Power of Positive Thinking. What David Brooks has labeled in The Road to Character as the age of “the Big Me,” McKenzie tells us, began two centuries ago with the election of Andrew Jackson.

We’ll look at that story from We the Fallen People in my next post.

Image by Wenhan Cheng from Pixabay

Thank you for this, Andy! Very thought provoking. The parts of it that note the problem of our fallenness bring to mind David French’s recent essay, “Our Nation Cannot Censor Its Way Back to Cultural Health.” Our core fallenness seems always to mess up our plans to develop a righteous and just society.

Yes. Fallenness. It’s pretty annoying, actually.