I was sitting around a table with some friends. How did the topic come up? I don’t quite recall.

We were talking about World War II, and Ralph said, “You can’t trust the Germans. Look what they’ve done in two world wars. And don’t say they’ve changed because skinheads and nationalism are on the rise there. We just should never have let them become an independent nation again. We should have carved up the country for good.”

I was a bit surprised to hear such ideas about a group of people who have little malice thrown at them these days. He didn’t sound angry. He wasn’t loud. He was outwardly calm, but I sensed there was emotion underneath.

I responded evenly by saying it seemed helpful to have them as allies, as a force for economic and political stability in central Europe. Clearly he still disagreed.

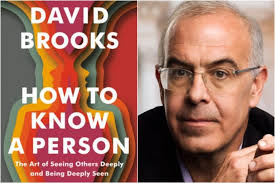

Then I remembered what I had just read in David Brooks’s new book, How to Know a Person. He told a story of being on a panel discussion with someone who had a very different view of the culture wars. Brooks responded not with anger or diatribe but by stating his side with a bit of cool dispassion.

Then I remembered what I had just read in David Brooks’s new book, How to Know a Person. He told a story of being on a panel discussion with someone who had a very different view of the culture wars. Brooks responded not with anger or diatribe but by stating his side with a bit of cool dispassion.

Later Brooks realized this was the wrong approach. Instead he should have at least asked more questions about what the other person thought and why.

Taking Brooks’s lead, I decided I too was wrong and that the important thing in this moment was not to try to change Ralph’s mind, not to correct him, however wrong his attitudes might be. My job first was to listen to him, get to know him, and maybe love him a little better.

So I started asking some questions, genuinely wanting to know more: “What’s behind your thoughts here? When and how did you first start to think this way?” And quietly he began to tell us more of his story.

His father and uncles had been in the war. What they saw and went through was terrible. And his wife had been born in central Europe. Her family had suffered at the hands of the Germans for multiple generations.

Ralph was not speculating on geopolitics. For him, this was personal.

Brooks is a consummate journalist who is excellent at summarizing the best research of experts while telling stories of others and himself that move us and create understanding. While offering excellent material on how to get to know people as individuals, he reminds us that everyone is situated in a group, in a history, in a place. We also have to explore and appreciate those to truly hear others.

In a day of hyper reactions and extreme tribalism, we seem to have lost the vital art of conversation, of making friends, of connecting with others more than superficially. Brooks tells us how with practical, sensible wisdom.

I don’t remember the last time I had put the ideas of a book into practice so quickly as I did with Ralph. Before I would have just sat in stunned silence. But now I knew how to respond positively. How to Know a Person is that kind of book, a book worth rereading.

First, Paul introduces this section on husbands and wives with, “Submit to one another out of reverence for Christ.” Submission for Paul is mutual, not just something a wife offers her husband.

First, Paul introduces this section on husbands and wives with, “Submit to one another out of reverence for Christ.” Submission for Paul is mutual, not just something a wife offers her husband.  Years ago my wife Phyllis felt stunted in her spiritual life by the church we were in. I took that seriously, even though I liked the church. I liked the people. I liked the music. I liked the preaching. It was great for me. After many months of discussion and prayer, however, we were not able to resolve the issue. Then I remembered that Ephesians 5 meant that my wife’s spiritual well-being came before mine. I had to die. So I told her, “It’s up to you. If you want us to go to a different church, we will. I want what’s best for you.”

Years ago my wife Phyllis felt stunted in her spiritual life by the church we were in. I took that seriously, even though I liked the church. I liked the people. I liked the music. I liked the preaching. It was great for me. After many months of discussion and prayer, however, we were not able to resolve the issue. Then I remembered that Ephesians 5 meant that my wife’s spiritual well-being came before mine. I had to die. So I told her, “It’s up to you. If you want us to go to a different church, we will. I want what’s best for you.” Humanity, male and female, is created in God’s image. This is emphasized by repeating it in three slightly different ways. Together we bear God’s image. And what does it mean to do that? The answer is in the very next verse:

Humanity, male and female, is created in God’s image. This is emphasized by repeating it in three slightly different ways. Together we bear God’s image. And what does it mean to do that? The answer is in the very next verse: But there’s something else you should know about my dad. He was a confirmed bachelor for forty-six years. He had decided he would not get married because he had never seen a happily married couple. And as he told us, the reason for the unhappiness was always money.

But there’s something else you should know about my dad. He was a confirmed bachelor for forty-six years. He had decided he would not get married because he had never seen a happily married couple. And as he told us, the reason for the unhappiness was always money.  Extravagance wasn’t the lesson I got from this episode or from watching my parents for decades. After all, they had both lived through the Depression, and frugality was baked into my DNA.

Extravagance wasn’t the lesson I got from this episode or from watching my parents for decades. After all, they had both lived through the Depression, and frugality was baked into my DNA.  Social

Social To keep great conversations and relationships growing, it’s key to be nonjudgmental, to ask follow-up questions, and not be too quick to give our perspective.

To keep great conversations and relationships growing, it’s key to be nonjudgmental, to ask follow-up questions, and not be too quick to give our perspective.

♦ Reengage with lifelong friends. Admittedly it can be hard to make new friends. An easier but still very fruitful path might be to renew connections with old friends near and far. In recent years I’ve deliberately increased the emails to, calls and zooms with, and visits to several longstanding friends. Some I’ve had spotty contact with over the years, and some I hadn’t seen in decades. But I’ve so enjoyed the results of more regular connection with all of them.

♦ Reengage with lifelong friends. Admittedly it can be hard to make new friends. An easier but still very fruitful path might be to renew connections with old friends near and far. In recent years I’ve deliberately increased the emails to, calls and zooms with, and visits to several longstanding friends. Some I’ve had spotty contact with over the years, and some I hadn’t seen in decades. But I’ve so enjoyed the results of more regular connection with all of them.  Twenty-five years ago,

Twenty-five years ago,  But then how would I know where to contribute when a crisis arises? Simply by giving to a relief organization you trust on a regular basis, regardless of whether or not there is a special need. Such crises, sadly, happen often. Send your gift to someone like the

But then how would I know where to contribute when a crisis arises? Simply by giving to a relief organization you trust on a regular basis, regardless of whether or not there is a special need. Such crises, sadly, happen often. Send your gift to someone like the  With the blizzard still raging, our car was eventually able to limp to a nearby exit for a small town where Phyllis and I sheltered in a restaurant with our four young children, all of us dazed and uncertain what to do. As we were standing there among dozens of other stranded motorists, we heard rumors that the town was going to open up the local high school gym so people would have a place to stay that cold winter night.

With the blizzard still raging, our car was eventually able to limp to a nearby exit for a small town where Phyllis and I sheltered in a restaurant with our four young children, all of us dazed and uncertain what to do. As we were standing there among dozens of other stranded motorists, we heard rumors that the town was going to open up the local high school gym so people would have a place to stay that cold winter night. I could hardly believe it. We were the ones in need. We were the ones who had been helped, but somehow they were the ones who were blessed.

I could hardly believe it. We were the ones in need. We were the ones who had been helped, but somehow they were the ones who were blessed.