We all read the Bible from our own viewpoint, from within our own culture and background. Our circumstances make us ask certain questions we wouldn’t ask otherwise. We could consider this a disadvantage. How could we know what the Bible really said when we are inevitably limited? But what if this were a blessing? What if this drawback allowed God to speak with truth and power to our particular situations?

Consider Martin Luther. His context of an often legalistic and corrupt church made him ask certain questions of the Bible about salvation. Or Dietrich Bonhoeffer. His experiences with the black church in Harlem and Hitler’s regime in Germany drove him to ask certain questions about how Christians and the church should relate to the government. Their answers did not encompass all the Bible said, but they were true.

Consider Martin Luther. His context of an often legalistic and corrupt church made him ask certain questions of the Bible about salvation. Or Dietrich Bonhoeffer. His experiences with the black church in Harlem and Hitler’s regime in Germany drove him to ask certain questions about how Christians and the church should relate to the government. Their answers did not encompass all the Bible said, but they were true.

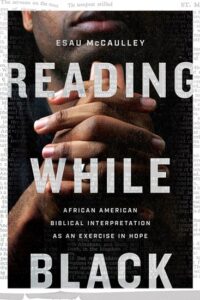

This is what Esau McCaulley offers in Reading While Black. He found himself both feeling at home and not feeling at home with black and white progressives as well as with black and white evangelicals. Could he forge a new path that was unapologetically black and unapologetically orthodox? With pain and hope he points the way to true answers.

Several years ago, when I heard Esau McCaulley offer initial thoughts on a theology of policing, I thought, “What an amazing, creative question to ask, and what an intriguing, substantive proposal he makes!” In this book McCaulley also asks: How should the church offer a political witness? What is a full-orbed view of justice? How can Blacks gain identity from Scripture? What should Blacks do with the rage they feel from the injustices they’ve experienced? Does the Bible justify slavery as some contended for centuries?

The insights he offers to these are many and stirring. For example, he reminds us that Romans 13 is not the only passage about attitudes toward government in the Bible. In Luke 13:32-33 Jesus shows no deference toward a particular ruler. In Luke 1:51-53 Mary looks forward to governments which are not run by prideful men but which help the poor (echoing Isaiah).

He also highlights the beginning of the fulfillment of God’s promise that all nations would be blessed through Abraham when Jacob adopts Joseph’s two sons (his two biracial, half-African sons!) as his own in Genesis 48:3-5. Can those of African descent especially find their place in God’s promises? Indeed!

He also highlights the beginning of the fulfillment of God’s promise that all nations would be blessed through Abraham when Jacob adopts Joseph’s two sons (his two biracial, half-African sons!) as his own in Genesis 48:3-5. Can those of African descent especially find their place in God’s promises? Indeed!

Then there is the question of black rage. I found his thoughts on the psalms of lament and imprecatory psalms to be some of the most powerful reflections he has to offer in the book.

The answers that Luther and Bonhoeffer found in the Bible are true—but they aren’t exactly the same. McCaulley simply asks for the same privilege that was accorded these gentlemen to struggling with difficult texts and difficult contexts.

Yet if everyone comes to the Bible from a different place, how can we know what it really says? Should we stop asking what the central message of the Bible is? McCaulley says no. We should instead ask (as he does) which understanding “does justice to as much of the biblical witness as possible. There are uses of Scripture that utter a false testimony about God.” (p. 91).

Esau McCaulley wrote this important book for himself. As a result he has also written a necessary book for all of us.

—

I received a complimentary copy of this book from the publisher. My opinions are my own.

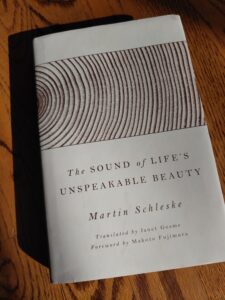

When a friend gave me his book, one of the most beautiful and profound works I’ve read, he wisely suggested I savor a few pages at a time. The depth of each page, of each paragraph, of each sentence made it worthwhile to do just that. Over the period of a few months I sojourned through this book.

When a friend gave me his book, one of the most beautiful and profound works I’ve read, he wisely suggested I savor a few pages at a time. The depth of each page, of each paragraph, of each sentence made it worthwhile to do just that. Over the period of a few months I sojourned through this book.

And what is the difference between giftables and gifts? Two extraneous syllables and four unnecessary letters! What could possibly justify creating a gratuitous adjective just to make it into a noun? And don’t get me started on using too many exclamation points!

And what is the difference between giftables and gifts? Two extraneous syllables and four unnecessary letters! What could possibly justify creating a gratuitous adjective just to make it into a noun? And don’t get me started on using too many exclamation points!

We have all become very attuned to how things look. Our design sensitivities have been heightened in recent decades. Apple has probably had as much to do with this as anything with the beautiful minimalism that distinguishes its products. So, yes, a blog or website has to have a certain level of sophistication and eye appeal. But it doesn’t have to be expensive or over the top.

We have all become very attuned to how things look. Our design sensitivities have been heightened in recent decades. Apple has probably had as much to do with this as anything with the beautiful minimalism that distinguishes its products. So, yes, a blog or website has to have a certain level of sophistication and eye appeal. But it doesn’t have to be expensive or over the top.

From a Western perspective, we might see patronage as creating unhealthy dependence, even being oppressive. But those inside see it as providing protection, meeting needs, giving security. Yes, it can be abused, but the problem then is not the system but the people in it.

From a Western perspective, we might see patronage as creating unhealthy dependence, even being oppressive. But those inside see it as providing protection, meeting needs, giving security. Yes, it can be abused, but the problem then is not the system but the people in it.

Gladwell begins and ends the book with the story of Sandra Bland, the 28-year-old African American who in 2015 was stopped for a minor traffic infraction, arrested, and committed suicide in jail three days later. He methodically unpacks the recorded July 10 encounter with State Trooper Brian Encinia.

Gladwell begins and ends the book with the story of Sandra Bland, the 28-year-old African American who in 2015 was stopped for a minor traffic infraction, arrested, and committed suicide in jail three days later. He methodically unpacks the recorded July 10 encounter with State Trooper Brian Encinia.

After some time, and having wasted everything, he is destitute and starving. In desperation he decides to return to his father, thinking to make an abject apology and ask for mercy.

After some time, and having wasted everything, he is destitute and starving. In desperation he decides to return to his father, thinking to make an abject apology and ask for mercy.