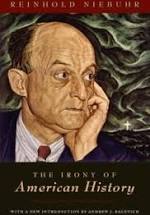

In a day when so many of us think we are RIGHT while so many others are WRONG, Reinhold Niebuhr’s neglected classic, The Irony of American History, deserves wide reading. Published the year I was born (1952), in the context of a world dominated by the sharply defined conflict between democracy and communism, its clear message is still important today.

As much as we would like to change the world (regardless of our ideals from the right or left), we inevitably bump into both our finiteness and our selfishness (or guilt, as Niebuhr calls it). When we ignore these limitations, trouble inevitably follows, sometimes tragically on a massive scale.

As much as we would like to change the world (regardless of our ideals from the right or left), we inevitably bump into both our finiteness and our selfishness (or guilt, as Niebuhr calls it). When we ignore these limitations, trouble inevitably follows, sometimes tragically on a massive scale.

The problem is that in our idealism we are “too blind to the curious compounds of good and evil in which the actions of the best men and nations abound” (p. 133). Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn echoed Niebuhr when he famously said, “The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either – but right through every human heart.”

The world is just immensely more complicated than we can imagine or give credit for. We forget, as Niebuhr says, that we are not just a creator of history but also its creature. Therefore, our overly energetic attempts to control it are sure to be met with disappointment or worse.

Throughout the book Niebuhr is a penetrating critic of communism’s flaws and failings, saying, for example, “Communism is a vivid object lesson in the monstrous consequences of moral complacency about the relation of dubious means to supposedly good ends” (p. 5). Yet he is also clear-eyed about how the American experiment can go haywire.

Throughout the book Niebuhr is a penetrating critic of communism’s flaws and failings, saying, for example, “Communism is a vivid object lesson in the monstrous consequences of moral complacency about the relation of dubious means to supposedly good ends” (p. 5). Yet he is also clear-eyed about how the American experiment can go haywire.

Free market thinking, for example, is very aware of the dangers of political and military power (especially seeking to limit the former) but downplays the reality of economic power, and sees little need to limit that. Part of the pragmatic virtue (and irony) of the American system is that we were able to recognize this and act on it at least somewhat. The labor movement and the New Deal of the last century created more financial equity and justice while still allowing capitalism to continue to dominate our theories.

Writing about the early 20th century he said, “The significant point in the American development is that here, no less than in Europe, a democratic political community has had enough virtue and honesty to disprove the Marxist indictment that government is merely the instrument of privileged classes” (p. 100).

America’s potential problems extend into other realms as well. “The American situation is such a vivid symbol of the spiritual perplexities of modern man, because the degree of American power tends to generate illusions to which a technocratic culture is already too prone. This technocratic approach to problems of history . . . accentuates a very old failing in human nature: the inclination of the wise, or the powerful, or the virtuous, to obscure and deny the human limitations in all human achievements and pretensions” (p. 147).

Niebuhr’s final chapter lays out what he means by irony—how two contrasting elements come together in a person or a nation with one arising from the other. A strength also contains a hidden weakness, for example. He goes on to highlight the foundation for this view of history, which comes from the biblical perspective of a “divine judge who laughs at human pretensions without being hostile to human aspirations” (p. 155).

Humility in spirit and modesty in ambition is not a message corporate kingpins, political powerbrokers, or even many humanitarian heroes want to hear. Such restraint does not suit them. Nor does pragmatism seem to rally a constituency as fervently as zealous idealism.

Yet his message is essential. That doesn’t mean we have no hope. Rather our hope and ideals are to be seasoned with realism about the world and with humility about ourselves.

One exception is reading. One tool I’ve found that helps keep me making progress is the Goodreads Reading Challenge. Goodreads is social networking site that is just about books. Friends post what they want to read, what they have read, give books a rating, and sometimes offer a review. I don’t try to get thousands of “friends.” Just a few hundred is plenty.

One exception is reading. One tool I’ve found that helps keep me making progress is the Goodreads Reading Challenge. Goodreads is social networking site that is just about books. Friends post what they want to read, what they have read, give books a rating, and sometimes offer a review. I don’t try to get thousands of “friends.” Just a few hundred is plenty. In recent years I’ve aimed at about fifty, and I’ve hit that target. This year I only read forty. That’s no cause to beat myself up. I’m sure I’ve been reading more than I would have otherwise just because that target is out there.

In recent years I’ve aimed at about fifty, and I’ve hit that target. This year I only read forty. That’s no cause to beat myself up. I’m sure I’ve been reading more than I would have otherwise just because that target is out there.

A few days later, when Mary and Joseph present the infant Jesus in the temple, they were met by an old man named Simeon. God had promised him he’d see the Messiah before he died. When he saw the trio he took Jesus in his arms and said:

A few days later, when Mary and Joseph present the infant Jesus in the temple, they were met by an old man named Simeon. God had promised him he’d see the Messiah before he died. When he saw the trio he took Jesus in his arms and said:

Advice That’s Out of This World

Advice That’s Out of This World

Throughout the book Niebuhr is a penetrating critic of communism’s flaws and failings, saying, for example, “Communism is a vivid object lesson in the monstrous consequences of moral complacency about the relation of dubious means to supposedly good ends” (p. 5). Yet he is also clear-eyed about how the American experiment can go haywire.

Throughout the book Niebuhr is a penetrating critic of communism’s flaws and failings, saying, for example, “Communism is a vivid object lesson in the monstrous consequences of moral complacency about the relation of dubious means to supposedly good ends” (p. 5). Yet he is also clear-eyed about how the American experiment can go haywire.

His final two chapters are especially valuable on how to read Daniel as 21st-century Christians in hostile cultures. He notes there is no “one-size-fits-all formula for how . . . to interact with powerful forces that are not friendly to our religious values.” Sometimes Daniel and his friends respond only in private and sometimes in public. Sometimes they seek to persuade rather than confront. “The one thing that is clear and consistent is that they do not go out of their way to offend the authorities” (148). Instead they use wisdom and civility while remaining faithful in difficult circumstances.

His final two chapters are especially valuable on how to read Daniel as 21st-century Christians in hostile cultures. He notes there is no “one-size-fits-all formula for how . . . to interact with powerful forces that are not friendly to our religious values.” Sometimes Daniel and his friends respond only in private and sometimes in public. Sometimes they seek to persuade rather than confront. “The one thing that is clear and consistent is that they do not go out of their way to offend the authorities” (148). Instead they use wisdom and civility while remaining faithful in difficult circumstances.  Some of you who subscribe to Andy Unedited have mentioned that the font size is small in the email alert you receive. If you just click on the headline of the blog found in the email, you will be sent to the blog website which is much more readable. (So, for example, if you get this in an email, put your cursor on “Tuesday Round Up” in the email and then click! Easy as eating pumpkin pie.)

Some of you who subscribe to Andy Unedited have mentioned that the font size is small in the email alert you receive. If you just click on the headline of the blog found in the email, you will be sent to the blog website which is much more readable. (So, for example, if you get this in an email, put your cursor on “Tuesday Round Up” in the email and then click! Easy as eating pumpkin pie.) My wife and I recently rented the DVD of this gripping story of two British soldiers in World War I who make an amazing 24-hour journey to deliver a message that could save hundreds of lives. The unusual use of only one camera during the entire film heightens not only the immersive immediacy of the movie but the dogged courage of this pair.

My wife and I recently rented the DVD of this gripping story of two British soldiers in World War I who make an amazing 24-hour journey to deliver a message that could save hundreds of lives. The unusual use of only one camera during the entire film heightens not only the immersive immediacy of the movie but the dogged courage of this pair.

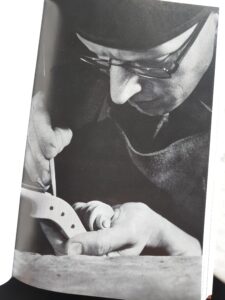

When a friend gave me his book, one of the most beautiful and profound works I’ve read, he wisely suggested I savor a few pages at a time. The depth of each page, of each paragraph, of each sentence made it worthwhile to do just that. Over the period of a few months I sojourned through this book.

When a friend gave me his book, one of the most beautiful and profound works I’ve read, he wisely suggested I savor a few pages at a time. The depth of each page, of each paragraph, of each sentence made it worthwhile to do just that. Over the period of a few months I sojourned through this book.

And what is the difference between giftables and gifts? Two extraneous syllables and four unnecessary letters! What could possibly justify creating a gratuitous adjective just to make it into a noun? And don’t get me started on using too many exclamation points!

And what is the difference between giftables and gifts? Two extraneous syllables and four unnecessary letters! What could possibly justify creating a gratuitous adjective just to make it into a noun? And don’t get me started on using too many exclamation points!