Angie Kim has a great message. Unfortunately, she wrapped it in an unattractive package.

Because we are human, she reminds us, we tend to carry stereotypes with us about people who are disabled. Think—talking louder to someone in a wheelchair when clearly the issue isn’t being hard of hearing.

Kim’s novel Happiness Falls alerts us to one in particular—assuming that people with physical disabilities also have mental disabilities. We may find ourselves unnecessarily talking to them more slowly or with simpler vocabulary or maybe talking about them as if they are not in the room at all.

We all need these reminders. It’s too bad that Kim serves up this healthy nourishment in an unpalatable soup. How so? The first-person narrator of Kim’s story is an immature, self-absorbed, mentally scattered person who routinely destroys evidence and obstructs justice regarding a potential crime. It is hard to be sympathetic with someone like that, and it is just too annoying and tiresome to stay inside the mind of such a person for 400 pages.

The author would have been better off writing the book in third-person omniscient or writing each part of the book from the first-person perspective of a different character in the story—the mother, the brother, the detective, the therapist, the person who is disabled. I would guess that the editor suggested such a shift, a shift the author sadly rejected.

That’s probably why, not typical for a novel, we find a lot of explanatory footnotes in the book. It’s the only way the editor could convince the author to get at least some of the extraneous, highly detailed reflections out of the narrative. But it was not enough to salvage the book, I fear.

The lesson here for writers is: choose your rut carefully. Especially for longer pieces like books, the tone had better not be too intense—whether too sweet or too depressed, too hyper or too relaxed, too mysterious or too detailed. Otherwise readers may not appreciate the value of what you have to say.

If you want readers to stick with you, when it comes to tone, less is more.

—

Image by WikimediaImages from Pixabay

So what did I do as his editor? I asked for no revisions whatsoever and published the book as it was. Why?

So what did I do as his editor? I asked for no revisions whatsoever and published the book as it was. Why? After waiting a moment and hearing nothing, he said, “Ok, then,” and with a wry smile that impishly suggested we had had our chance and wasted it, he began.

After waiting a moment and hearing nothing, he said, “Ok, then,” and with a wry smile that impishly suggested we had had our chance and wasted it, he began. Phase one is acquisition editing. An editor’s role here is to sign up authors to provide articles, blogs, books, or other written material. This is likely the first gatekeeper a writer encounters. Sometimes editors solicit pieces from writers they know, and sometimes writers come to editors with ideas. This phase has been jokingly (derisively?) referred to as “belly editing” for the legendary lunch meetings between editors and authors.

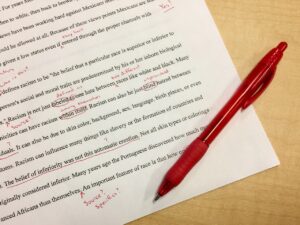

Phase one is acquisition editing. An editor’s role here is to sign up authors to provide articles, blogs, books, or other written material. This is likely the first gatekeeper a writer encounters. Sometimes editors solicit pieces from writers they know, and sometimes writers come to editors with ideas. This phase has been jokingly (derisively?) referred to as “belly editing” for the legendary lunch meetings between editors and authors.  The final phase is copyediting which deals with grammar, spelling, punctuation, house style, and format. Fact checking may arise here or perhaps at the line editing stage. Sometimes line editing and copyediting will be done simultaneously by a single person, collapsing these last two phases into one. After each stage authors are normally given opportunity to review the editing, respond to questions and suggestions, and to make further revisions.

The final phase is copyediting which deals with grammar, spelling, punctuation, house style, and format. Fact checking may arise here or perhaps at the line editing stage. Sometimes line editing and copyediting will be done simultaneously by a single person, collapsing these last two phases into one. After each stage authors are normally given opportunity to review the editing, respond to questions and suggestions, and to make further revisions.

A colleague, Jim Hoover, often said, “An editor is the author’s advocate to the reader—and the reader’s advocate to the author.” The job of editors is not to shape manuscripts the way they would write them. Rather when alerting authors to potential problems, editors aim to show authors what questions people might raise the first time they read the text. That is just virtually impossible for authors to do who are overly familiar with what they’ve written. “Isn’t it obvious?” No. Not always.

A colleague, Jim Hoover, often said, “An editor is the author’s advocate to the reader—and the reader’s advocate to the author.” The job of editors is not to shape manuscripts the way they would write them. Rather when alerting authors to potential problems, editors aim to show authors what questions people might raise the first time they read the text. That is just virtually impossible for authors to do who are overly familiar with what they’ve written. “Isn’t it obvious?” No. Not always.

And what is the difference between giftables and gifts? Two extraneous syllables and four unnecessary letters! What could possibly justify creating a gratuitous adjective just to make it into a noun? And don’t get me started on using too many exclamation points!

And what is the difference between giftables and gifts? Two extraneous syllables and four unnecessary letters! What could possibly justify creating a gratuitous adjective just to make it into a noun? And don’t get me started on using too many exclamation points! You can probably rewrite 90% of these sentences in active voice. For example,

You can probably rewrite 90% of these sentences in active voice. For example, Weak: The reason is because Facebook is trying to suck all the DNA out of my body.

Weak: The reason is because Facebook is trying to suck all the DNA out of my body.