The story of Christian publishing in the last hundred years is one of spunky start-ups and massive conglomerates, of individual faith and social movements, of passing fads and foundational convictions. It is also a story little told.

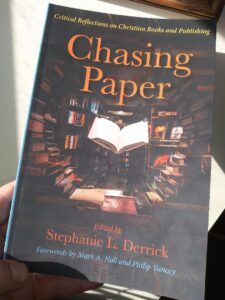

Helping fill that gap is Chasing Paper edited by independent scholar Stephanie Derrick. With forewords by Mark Noll and Philip Yancey as well as twenty brief essays (disclosure: including one I wrote), we hear from key participants whose work helped shape not only their publishing houses but also thousands of books issued in the last sixty years.

Helping fill that gap is Chasing Paper edited by independent scholar Stephanie Derrick. With forewords by Mark Noll and Philip Yancey as well as twenty brief essays (disclosure: including one I wrote), we hear from key participants whose work helped shape not only their publishing houses but also thousands of books issued in the last sixty years.

I was most impressed by the international scope of the collection. The global range of the enterprise is well represented with inside looks at Christian publishing in Brazil, sub-Saharan Africa, Pakistan, the Philippines, Peru, Vatican City, Canada, England, and the United States. The variety of religious communities is also significant, including Catholic as well as Protestant mainline, evangelical, African-American, and Pentecostal.

Most contributors take the approach of memoir, which allows for appropriate storytelling that makes for a quite readable volume. But they do not neglect the social, cultural, economic, and religious context of their work. These broader reflections are illuminating. The authors also relay the specific strategies they employed, strategies which could trigger creative and effective ideas for publishers and authors today who have different contexts with different but similar difficulties.

Peter Dwyer of Liturgical Press, for example, recalled how a dozen years ago he divided the challenges they faced into short-term (the economy of the Great Recession), medium-term (the business model required to deal with e-publishing and Amazon), and long-term (the Catholic Church with its clergy shortage and abuse scandals). Joseph Sinasac’s piece on publishing in Canada also offers a valuable array of strategies for facing the sea changes of recent decades.

Publishers love giving authors an opportunity to tell their stories. Here’s a book that gives publishers a chance to tell their own.

Whole genres even borrow from prior genres. Don’t many sci fi books and movies owe a great debt of gratitude to the old Western? What is different is combining two genres into one.

Whole genres even borrow from prior genres. Don’t many sci fi books and movies owe a great debt of gratitude to the old Western? What is different is combining two genres into one. I knew that in the book Dante is taken on a tour of hell with the ancient Roman poet Virgil as his guide. The best-known line, “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here,” greeted me as it greeted Dante on entering the underworld. There he found descending circles of the damned for such sins as lust, greed, violence, fraud, and betrayal.

I knew that in the book Dante is taken on a tour of hell with the ancient Roman poet Virgil as his guide. The best-known line, “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here,” greeted me as it greeted Dante on entering the underworld. There he found descending circles of the damned for such sins as lust, greed, violence, fraud, and betrayal. It would be like integrating the Star Wars universe or the world of Harry Potter into a biblical cosmology, where Darth Vader and Dumbledore both find themselves under the sway of a powerful Creator God who nonetheless uses sacrifice to resolve all storylines, reconcile all things, renew hope, and make everything right.

It would be like integrating the Star Wars universe or the world of Harry Potter into a biblical cosmology, where Darth Vader and Dumbledore both find themselves under the sway of a powerful Creator God who nonetheless uses sacrifice to resolve all storylines, reconcile all things, renew hope, and make everything right. After waiting a moment and hearing nothing, he said, “Ok, then,” and with a wry smile that impishly suggested we had had our chance and wasted it, he began.

After waiting a moment and hearing nothing, he said, “Ok, then,” and with a wry smile that impishly suggested we had had our chance and wasted it, he began. Over a hundred and twenty years ago, Edith Wharton, the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize, also suffered from this common malady. In 1899 she wrote to her publisher,

Over a hundred and twenty years ago, Edith Wharton, the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize, also suffered from this common malady. In 1899 she wrote to her publisher,  “You can cheer on the other girls. You can listen to what Coach says and do it immediately. You can decide not to get down on yourself if you make a mistake but instead try to do better next time. That’s attitude.

“You can cheer on the other girls. You can listen to what Coach says and do it immediately. You can decide not to get down on yourself if you make a mistake but instead try to do better next time. That’s attitude.

As 2004 concluded and 2005 began, national recognition came in a variety of high-profile ways to the author who had perhaps defined IVP more than any other over the decades. In the November 30 issue of the New York Times, columnist and commentator David Brooks wrote a

As 2004 concluded and 2005 began, national recognition came in a variety of high-profile ways to the author who had perhaps defined IVP more than any other over the decades. In the November 30 issue of the New York Times, columnist and commentator David Brooks wrote a