Last month, just about a year after my wife Phyllis died, I reread her book Handbook for Caring People, now out of print. I once again saw how this book reflected her own life of being deeply attuned to the needs of people—emotionally, physically, spiritually. I wasn’t the only one who thought she was perhaps the most caring person they’d ever known. So did dozens and hundreds of others.

Phyllis didn’t show her concern only when people were overtly hurting. She took delight in getting to know everyone she encountered—on a bus, standing in line, sitting in a park. Because of her genuine interest and ready laugh, they were quite willing to engage her in conversation. People just felt better about life and themselves after being with Phyllis.

Phyllis didn’t show her concern only when people were overtly hurting. She took delight in getting to know everyone she encountered—on a bus, standing in line, sitting in a park. Because of her genuine interest and ready laugh, they were quite willing to engage her in conversation. People just felt better about life and themselves after being with Phyllis.

Professionally, as a nurse she had hands-on experience dealing with the physical concerns of patients. But she cared about the whole person, and if patients gave evidence of emotional or spiritual needs, she was there for them.

When a man said he was afraid he wouldn’t make it through surgery, she didn’t ignore it or brush it off. She took time, asked questions and listened deeply. When she had found another patient sitting on the side of her bed crying, and a chair that had been thrown against a wall lying sideways on the floor, she took time to stop and gently ask, “What happened?”

Over the years that she worked with a Christian university ministry, students received the same care and attention—about academic stresses, problems at home, relationship issues, questions about God.

When Phyllis retired, she wondered what she would do next. After taking several months to see what her new rhythms of life might be, she eventually felt guided to obey Jesus in three particular ways—to feed the hungry, care for widows, and visit those in prison. And she did. She began volunteering once or twice a week at the food pantry our church operates, which helps feed hundreds of people every month.

In addition, she began giving more focused attention to an elderly widow who lived on our block. She played board games with her and brought over meals once a week or more.

In addition, she began giving more focused attention to an elderly widow who lived on our block. She played board games with her and brought over meals once a week or more.

Finally, she volunteered with JUST, an organization that works within the DuPage County Correctional Facility. They offered dozens of different classes a week on spiritual enrichment, addiction recovery, education, vocational and life skills. Every Friday morning, as she went to lead a Bible study for women inmates, she would tell me with a grin, “I’m going to jail now!”

She especially loved meeting with these women who were awaiting trial. These were people without pretense who knew they were broken. She told remarkable stories of those at the extremities of life. One said she thought jail saved her life. Otherwise she would be out on the street, and likely not survive that. Another put her faith in Christ, and Phyllis saw a striking transformation in the next weeks.

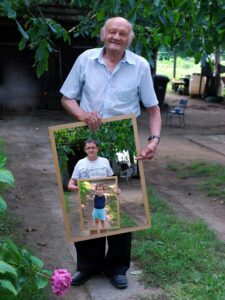

Over the almost fifty years I knew her, Phyllis had a massive impact on me. She shaped a nerd who was always in his head into someone who gained a habit for hospitality and for creating welcoming spaces for people. We constantly had people staying in our home for a night, a week, even months at a time.

Phyllis was always ready with an offer of a bed and a meal and friendship and laughter. Whenever a need arose, Phyllis would ask me about it. I’d roll my eyes (sometimes inwardly, often outwardly) wondering if I always had to stretch like this to include others into our household. But we did, and I was better for it.

Phyllis showed me how to love others with the love of Jesus in a way that they loved too.

Certainly we had an influence on one another. But while I may have widened her world, she widened my soul.

Then Cooper said, “Can I ask a question? Do you feel you are entitled to the truth?”

Then Cooper said, “Can I ask a question? Do you feel you are entitled to the truth?” But why does “We Three Kings” mix the minor-like Aeolian key with a chorus that is major? Is it to give the carol a Middle Eastern flavor in light of the magi coming from the east? Perhaps.

But why does “We Three Kings” mix the minor-like Aeolian key with a chorus that is major? Is it to give the carol a Middle Eastern flavor in light of the magi coming from the east? Perhaps.

In this way Bilbro offers more ways forward than Postman. “Instead of allowing the news to create our communities, Christians should seek to help their communities create the news.” This can begin with the simple act of walking our neighborhoods rather than isolating ourselves in cars or behind screens. On another level we can, for example, pursue redemptive publishing by reading, he suggests, things like Civil Eats, American Conservative, The Atlantic, Commonweal, Hedgehog Review and more.

In this way Bilbro offers more ways forward than Postman. “Instead of allowing the news to create our communities, Christians should seek to help their communities create the news.” This can begin with the simple act of walking our neighborhoods rather than isolating ourselves in cars or behind screens. On another level we can, for example, pursue redemptive publishing by reading, he suggests, things like Civil Eats, American Conservative, The Atlantic, Commonweal, Hedgehog Review and more.

Early on a priest says he can make sense of it (as God’s judgment) though at the end his theology fails when he sees a small child die after prolonged suffering. A conman makes sense of it by taking advantage of the hardships of others only to revert to depression when the plague lifts. A writer plows ahead with his novel, day by day and month by month, yet never gets beyond the first sentence. A doctor seeks meaning by doggedly helping others even when his efforts often have little effect.

Early on a priest says he can make sense of it (as God’s judgment) though at the end his theology fails when he sees a small child die after prolonged suffering. A conman makes sense of it by taking advantage of the hardships of others only to revert to depression when the plague lifts. A writer plows ahead with his novel, day by day and month by month, yet never gets beyond the first sentence. A doctor seeks meaning by doggedly helping others even when his efforts often have little effect.

Why? We live in a world that often seems so random and chaotic. None of us knows who will get cancer next, be in a car accident, or where the next war will break out. Experts famously fail in making such predictions. We can increase the odds of living a healthy life, but we have no guarantees.

Why? We live in a world that often seems so random and chaotic. None of us knows who will get cancer next, be in a car accident, or where the next war will break out. Experts famously fail in making such predictions. We can increase the odds of living a healthy life, but we have no guarantees. One exception is reading. One tool I’ve found that helps keep me making progress is the Goodreads Reading Challenge.

One exception is reading. One tool I’ve found that helps keep me making progress is the Goodreads Reading Challenge.  In recent years I’ve aimed at about fifty, and I’ve hit that target. This year I only read forty. That’s no cause to beat myself up. I’m sure I’ve been reading more than I would have otherwise just because that target is out there.

In recent years I’ve aimed at about fifty, and I’ve hit that target. This year I only read forty. That’s no cause to beat myself up. I’m sure I’ve been reading more than I would have otherwise just because that target is out there. A few days later, when Mary and Joseph present the infant Jesus in the temple, they were met by an old man named Simeon. God had promised him he’d see the Messiah before he died. When he saw the trio he took Jesus in his arms and said:

A few days later, when Mary and Joseph present the infant Jesus in the temple, they were met by an old man named Simeon. God had promised him he’d see the Messiah before he died. When he saw the trio he took Jesus in his arms and said: